Culinary, cultural, and commercial contributions of Africans in London from Ridley Road to Rye Lane, from West Ham to Woolwich

📚 You can buy any book mentioned in this newsletter from my store on Bookshop.org

Life

Where does Black African life exist in London?

Our presence has been a constant for many centuries in Britain. In recent decades, Black African identity has evolved, ranging from Black to Afro-Caribbean to Black British. The government’s attempts at classifying its Black populations have been equally unsure. “BAME” is broadly agreed to create more problems than it solves, and has fallen out of official use. Black Africans, as a demographic visible to the government, has only existed since the 1991 census.

“Black UK residents directly drawn from Africa have only existed in an official sense for just over 30 years. Until the 1991 census introduced ‘Black African’ as an option on its identity menu, we were not considered worthy of specific categorisation.” — Settlers, pg. viii

The presence of communities originating from Nigeria to Namibia, Somalia to Senegal, or Congo to Kenya continues to have a lasting effect on British music, food, fashion, literature and acting. We dance to amapiano and eat jollof. We give praise in churches and pray in mosques — each combining to create surges of traffic up the Old Kent Road on a Sunday morning. We have looked on in awe as Stormzy took the stage at Glastonbury — that bastion of indie music, and marvelled at the raw emotion of I May Destroy You.

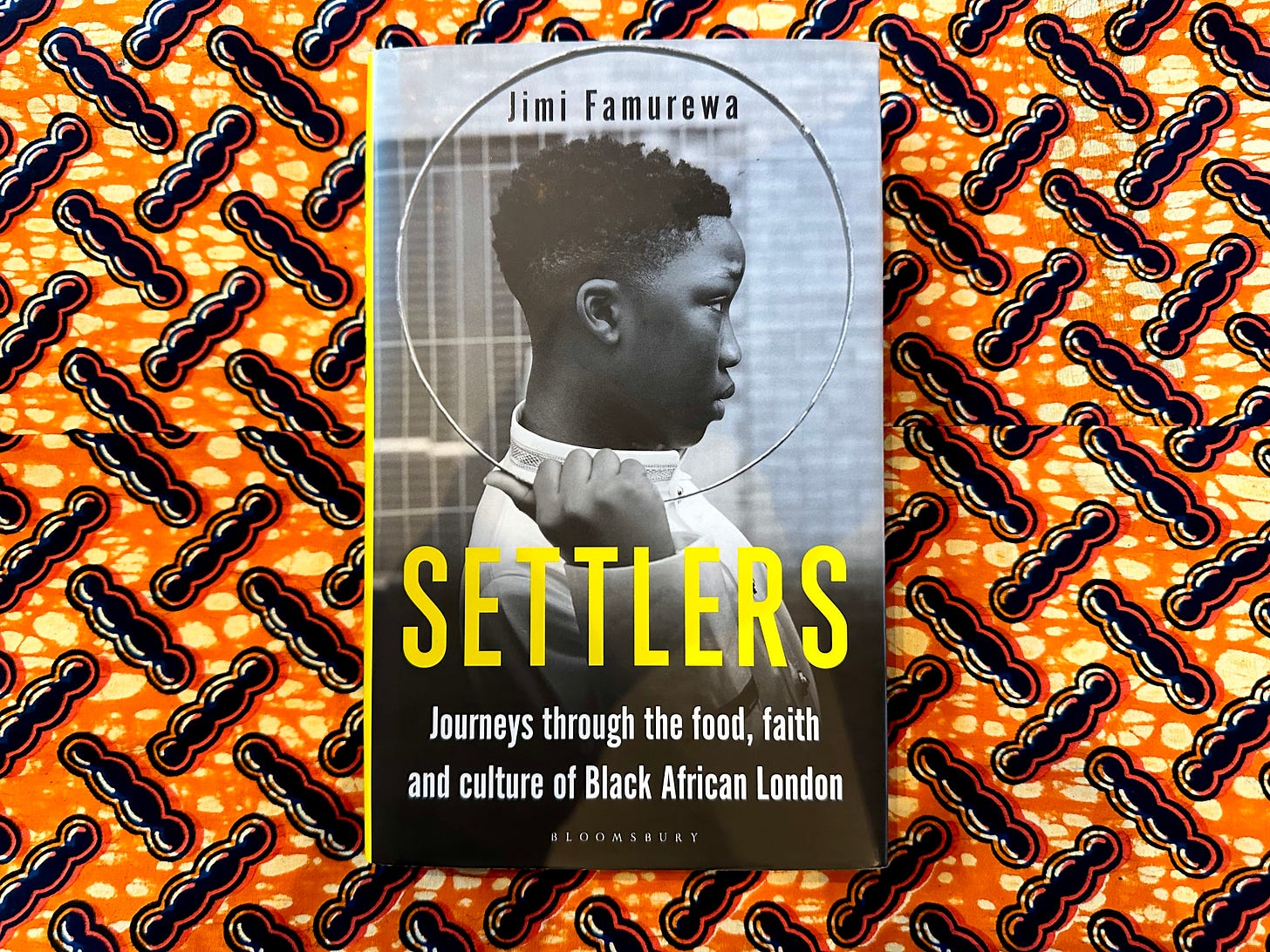

In Settlers, author Jimi Famurewa, takes us on a journey through the different neighbourhoods of London to document the stories of Black African life. Part history, memoir and reportage, the aromas, sounds and vibrations of our communities — of my community — come to life on the page.

The duality of Black African life in London comes to the fore, even as I write. Simultaneously an outsider and insider — African and British — there is a visibility and invisibility at play as these two sides of my identity — ethnic and administrative — jostle for eminence.

“The notion of settling denotes a sense of steadfastness, of compromise, and of claiming something as your own. It has a certain quiet defiance and reversal of colonial occupation that feels appropriate.”— Settlers, pg. xix

Black life is visible. It is audible. Black life is redolent. It takes up space and spills across the pavement. Yet despite its sensual persistence, Black African life in London can be moved on without leaving a trace. There are few historical monuments or cultural markers that testify to our lasting existence.

While the growth of African food is finally starting to gain wider critical appreciation, it is emblematic of the erasure and enclosure that surrounds many African communities and our food.

Food

Jimi Famurewa came to wider attention when he was appointed as the restaurant critic for London’s Evening Standard newspaper in 2020. For this reason, the role of Black African food is a central theme of Settlers, and the cultural position inhabited by the restaurant is closely examined.

Vittles has done much to capture the Sohofication of the London restaurant and was one of the more prominent publications to openly critique the cultural exclusion within food writing, and take on the myopic gaze of the fine dining industry — particularly its long-term resistance to accepting African food as haute cuisine. But this is only part of the story. Famurewa also alerts us to the impermanence of African food markets in the capital. From Ridley Road to Rye Lane, from West Ham to Woolwich — many markets and shopkeepers are tenants in precarious commercial settings, fighting against spiralling rents. Current proprietors struggle to convince their younger family members to take over — such is the pull of the City and tech for the next generation.

Understanding the church’s role — specifically Black African churches — is foundational. Church attendance has plummeted nationally in white British communities. A walk along the Old Kent Road or Camberwell Road on a Sunday morning paints a contrasting picture, as convoys of vehicles and packed buses rush their congregants to service. The social spaces for many Black African communities thrive in places of worship and culminate in communal meals that take place after services end. While it is true that the restaurant industry has been exclusionary, it is equally true that London’s finest assorted meat stews, jollof rice, tilapia, moin moin, spinach and egusi, and puff puff1 are being served in community halls on Sunday afternoons.

WASU

The part of Settlers that lingered with me and is emblematic of the impermanence of Black African presence in London’s built environment, is the story of the West African Students Union (WASU).

As growing numbers of students from Nigeria and Ghana came to study in London during the 1930s, a hostel was established at 62 Camden Road by Ladipo Solanke and his wife, Chief Opeolu Ogunbiyi (‘Mama WASU’). Black African students far from home found refuge, community and a taste of home behind these doors.

Part social club, restaurant and campaigning organisation, the existence of WASU pre-dates the first recognised African restaurant in London — the International Afro restaurant; the paucity of search engine results is a visual testimony of how our stories evade preservation and elide collective memory. It is also instructive into the history of African commercial public dining, or rather a description of why restaurants have not been a primary concern in some Black African communities. The food was secondary to having a meeting point and social hub.

WASU soon moved to larger premises at 1 South Villas, a leafy residential road filled with late-Victorian period townhouses — Professor Hakim Adi, above, provides one of the few contemporary resources about the house. South Villas springs from the north-eastern corner of Camden Square — an address more famous for its steady trickle of visitors on pilgrimage to Amy Winehouse’s former and final home at number 30.

Today, number 1 South Villas is a private residence. No external trace remains of the West African Students Union. In its time, WASU welcomed a young Kwame Nkrumah and played an important role in bringing together future African leaders who went on to form campaigns for independence in their home countries. WASU’s disappearance embodies the ease with which Black African existence loses its grip on the fabric of London.

Londoner

I began this review by listing many of the terms by which Black Africans have been defined by the government. However, I omitted one very important phrase by which many Black Africans define themselves — Londoner.

To be a Londoner is to exist in duality. One where at times, the Black African can be both a joyous majority and an isolated, simultaneously visible-invisible minority. The story of settling and migration is one that never truly ends — a point that Famurewa acknowledges in the final chapter, as he explores the continuing shifts of Black African migration towards bigger family homes in the outer zones of the city and beyond — places such as Erith and Thamesmead south of the river, or Southend and Tilbury north of the river.

In writing Settlers, Famurewa has gifted Black African Londoners a textual permanence that ensures our existence will never be lost or forgotten again.

Settlers: Journeys Through the Food, Faith and Culture of Black African London by Jimi Famurewa. Published in 2022 by Bloomsbury Publishing, 296 pages.

More from Jimi Famurewa

Jimi is the restaurant critic for London’s Evening Standard. Go and read his latest reviews, published every week.

‘I think of suya and I’m on a Lagos beach with Mum’: celebrating Nigeria’s spice dish (from The Guardian, 2022)

Where’s Home Really?, a podcast series where Jimi interviews different people in their public eye and learns about their personal stories and histories and how they define the meaning of home through a person, place and dish (2023 onwards)

Explore further

On Instagram

On Substack

Let’s zoom out for a minute and remind ourselves that there are Black communities thriving outside of London!

Emmanuelle Maréchal is a fashion industry professional writing Le Journal Curioso on Substack. In this article, which I think is a useful parallel to Settlers, she explores the myths and contradictions of being French and a Black Parisian woman.

“The Parisian woman is a myth we all grew up with, deeply rooted in France’s DNA. The problem is that it didn’t evolve with time, but above all, it doesn’t reflect the country’s social change. Walking in Paris streets, it is clear that the Parisian woman is Black, North African, Asian, South Asian, and so on.”

Listen

Black, African and British, a 4-episode radio series examining how Black African communities have influenced British life (via BBC Sounds, 8 January 2024, 28 mins each)

Transcripts are available for Matooke Goes With Everything.

Watch

A beautiful short film, by Adeyemi Michael, presents the Nigerian South London community through a magical perspective.

Resources

Black London: History, Art & Culture in over 120 places is a fantastic guidebook by Avril Nanton and Jody Burton that maps out monuments and places of interest about Black history in London. Take a day off and explore. You will be surprised by what you discover!

And if a book is too unwieldy, get their Black History London Map instead!

Read

Meet London's African churches — from warehouses to bingo halls by Chloe Dewe Mathews (Tate, 2014)

Brit(ish): On Race, Identity and Belonging by Afua Hirsch (Vintage Publishing, 2018, 384 pages)

African churches boom in London's backstreets – a picture essay by Simon Dawson / Reuters. Words by William Schomberg (from The Guardian, 2019)

Afropean: Notes from Black Europe by Johny Pitts (Penguin, 2019, 393 pages)

Black, Listed: Black British Culture Explored by Jeffrey Boakye (Dialogue, 2019, 416 pages)

Safe: 20 Ways to be a Black Man in Britain Today edited by Derek Owusu (Trapeze, 2019, 240 pages)

How the West African Students Union drove the anti-colonial agenda in 20th century London by Yosola Olorunshola (from Quartz, 2021)

A Mother Tongue by Axel Kacoutié (from Axel Kacoutié, 2022, transcript available)

Home Is Not A Place by Johny Pitts and Roger Robinson (William Collins, 2022, 160 pages)

West African Students’ Union (WASU) by Ekeoma Ugoezi Ezeh (from Black Past, 2022)

‘If we’re in the building, you’ll know about it’: For Black Boys, the dynamic, daring play wowing the West End by Jason Okundaye (The Guardian, 2023)

Is the future of Christianity African? by Tomiwa Owolade (New Statesman, 2023)

Mandem edited by Iggy London (Jacaranda Books, 2023, 228 pages)

OK, “Mandazi” if you’re East African! 😉

I had no idea that the ES had a new restaurant critic or about Jimi's work at all - thanks for this. I'll be checking out the podcast for sure...a treat to read to the end and see my conversation with Johny Pitts listed..thank u!

Thank you so much for sharing! I can’t wait to do a deep dive on the books and podcasts cited