Imagining a border-free world while critiquing the role that surveillance, databases and algorithms play in enacting racial and gender harms

📚 You can buy any book mentioned in this newsletter from my store on Bookshop.org

Border-free futures

Imagining a world without borders is a radical act of rebuilding that rejects the imposed hierarchies of a past colonial era.

From its outset, Against Borders invites us to accompany the authors in imagining a world without borders, fully aware that their resulting proposal is a beginning and requires more work before it can be realised as a practical reality.

Design is making changes within a set of constraints, however in the act of speculative world-building, we can consider questions that are usually out of normal creative reach using our knowledge of theory, supported by empirical, academic and artistic research.

Against Borders begins by establishing how borders, as an artefact, technology and activity each fail in their central tenet — to restrict the movement of people.

“If colonialism involved the imposition of rules, hierarchies and categories, from land borders to the gender binary, where before there were none or less; decoloniality requires the breaking down of borders and these systems of oppression.” — Against Borders, pg. 138

The nation-state intercepts certain migrants, and it is in the state’s gaze that the border acts in response to localised and geopolitical fears. And yet people continue to move, despite the presence and existence of borders.

Unequal distribution of capital and labour — a post-colonial legacy — is the catalyst for movement. In the face of a growing global climate crisis, relying on fixed borders will not stand up to the challenge of drought, flood and environmental disaster — none of which are constrained by national boundaries.

Technology of the border

A significant portion of Against Borders examines the technology and data infrastructures that facilitate the modern function of the border.

The nationality of your passport will likely have the greatest influence on where and when you encounter a border. For the British passport holder, an enforced border may appear to be absent in everyday life — most British citizens will only notice their encounter with its technology when entering or exiting a sea or airport — but the reality is that the technology of the border is a continuation of historical legacies of the state facing inwards to fix its gaze on the interior.

The desire to anticipate crime is closely associated with the development of intelligence-led policing in the UK. The post-IRA era in London closely followed by the 9/11 and 7/7 terrorist attacks, combined with a wider availability of computer vision and algorithmic surveillance technology, drove the capabilities of law enforcement to gather and store data at scale within London and other major cities across the UK and Europe. Automatic number plate recognition, ostensibly a technology for administering what surveillance scholar Gabriel Pereira terms “banal surveillance” for the administration of road toll charges (to name one example), has expanded in scope to form a digital dragnet against which nobody can opt-out.1

The tension between our understanding of the tangible artefacts of the border is hindered by its invisibility — it is this intangibility that assists the avoidance of critical scrutiny.

“Due to their technical complexity and lack of public understanding, [banal surveillance] also entails the difficulties of identifying problematic elements in such systems, where the most visible part is often not the most problematic. Banality inoculates against public oversight, even if it is not a deliberate strategy to evade scrutiny by actors involved in infrastructuring.” — From Banal Surveillance to Function Creep: Automated License Plate Recognition (ALPR) in Denmark, pg. 266

For the migrant, a border is a tangible and weighty entity. As computer vision, analytic and algorithmic technologies have increased in capabilities and scale, the scope of where a border can impose itself into everyday life has also expanded. For the migrant living within a nation foreign to their own, the border is no longer just an entry or exit point, but one that demands increased interaction and continual negotiation to satisfy the state’s demands. In the UK, the last two decades have seen the responsibility of policing this border fall more heavily onto the health service, schools, universities, employers and landlords.

“[Borders] follow people around, excluding them in various ways at different times, thus producing the precarity and disposability that characterises the migrant condition.” — Against Borders, pg. 5

While the technology of the policed border is a modern innovation, the desire for governments to control the movements of the people it views as suspicious or on the margins has been persistent. The UK’s Hostile Environment policy has done much to alert the wider citizen population of the punitive effects visited upon migrants from lower-income countries — particularly on people who are not racialised as White.

The conditional citizen

In Autoportrait, Molenbeek, 2007-2011, Hélène Amouzou produced a series of hand-printed photographs in which she appears phantom-like in sparse interiors. Her appearance suggests a liminal existence, a ghostly apparition that could be vaporised at any time and leave no trace. As a Togolese artist, Amouzou’s administrative acceptance took almost two decades before she gained Belgian citizenship. The visual metaphor of these photographs speaks directly to the precarity of African existence within the datafied societies of Europe.

Returning to Against Borders, the subject, history and technology of borders is one that equally fascinates and concerns me. When reflecting on my positionality as a British citizen born in England, racialised as Black, with parents who are both East African nationals — the link between birthplace and nationality has been conditional for the majority of my life, with protections that are weakening.

Such systems — designed systems — have been made, which also means they can be remade.

“... internal border controls are practices of racist classification and exclusion, even as their political focus can expand and shift to encompass populations (often ambivalently) categorised as ‘white’” — No Pass Laws Here! Internal Border Controls and the Global ‘Hostile Environment’, pg. 941

The co-authors of Against Borders argue strongly for abolition, as opposed to reform, of structurally discriminatory and oppressive technologies. The passport, as we know it, is only 104 years old. Its temporal roots are shallow. To better understand the histories and technological gaze of the border — especially how the Black subject is detected and captured in data — is one that deserves closer examination. I will expand upon this subject in my next newsletter, Fifteenth #4: On Borders, arriving in two weeks on Friday 15th March.

Against Borders: The Case for Abolition by Gracie Mae Bradley and Luke De Noronha. Published in 2022 by Verso Books, 184 pages.

More from the authors

A Logic of Dehumanisation by Gracie Mae Bradley (from Verso Blog, 2018)

Life after deportation: ’No one tells you how lonely you’re going to be’ by Luke de Noronha (from The Guardian, 2020)

Here’s why a border-free world would be better than hostile immigration policies by Gracie Mae Bradley and Luke De Noronha (from The Guardian, 2022)

Explore further

On Substack

Lou Mensah writes in Shade Art Review about The Photographer’s Green Book: Visual resource map. It is useful to understand borders from the perspective of the technologies that facilitate the surveilling of people at the margins. This interactive map is a fantastic resource that demonstrates the links between technology (in this case, photography), identity and identification.

Nothing sums up the misdirected and punitive gaze of border surveillance more than its hostility to food, or rather to ethnic food. To pack a nutritious meal, made with love is an aromatic connection to home. In this essay, Jacinta Mulders examines the oppressive nature of food policy at the borders, the humiliation of (mostly) Black and Brown travellers, and its reduction to subpar reality TV. I also urge you to take time to read the article “On Pothichoru“ for an oppositional viewpoint.

Listen

Resources

Interactive world map of visa-free travel, a map exposing the mismatch in travel freedoms by passport nationality.

Gordon Parks: Segregation Story, was exhibited at the High Museum in Atlanta, from 2014-15. The Gordon Parks Foundation also published a book expanding upon the original Life magazine article that Parks photographed for this trip. When discussing histories of segregation and internal borders, accompanying photos are often printed in black and white, which creates the illusion of a distant past. The histories captured here are not old — they are well within the lifetime of my parents. The rich colour of Gordon Parks’s photojournalism forcefully reminds us how recently these policies existed.

Magazine

Migrant (6-issue set, 2016-2019, €20 each; only issue 3 and issue 6 remain)

The Road to Nowhere (vol. 3, 2023, £20)

Read

The Politics of Design by Ruben Pater (BIS Publishers, 2016, 192 pages)

Lost in Media: Migrant Perspectives and the Public Sphere edited by Ismail Einashe and Thomas Roueché (Valiz, 2019, 167 pages)

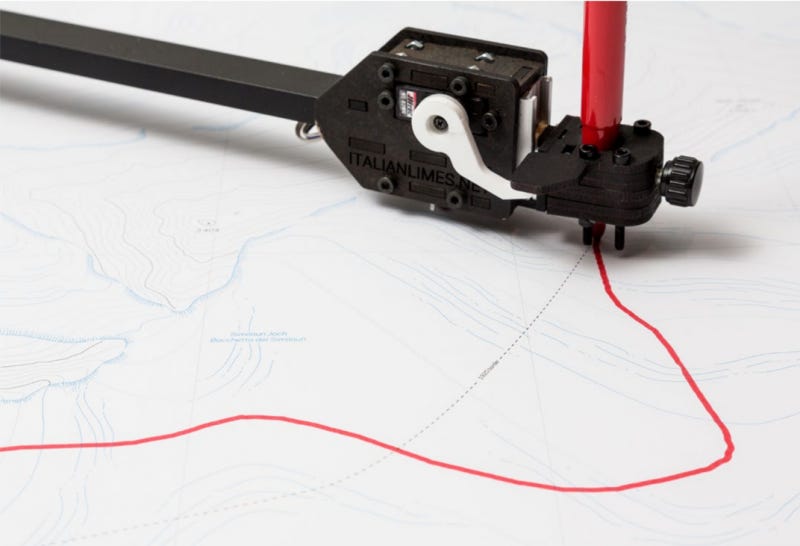

A Moving Border. Alpine Cartographies of Climate Change by Marco Ferrari, Elisa Pasqual and Andrea Bagnato (Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2019, 192 pages)

As the climate shifts, a border moves by Elza Bouhassira (EarthSky, 2020)

UN warns of impact of smart borders on refugees: ‘Data collection isn't apolitical’ by Katy Fallon (from The Guardian, 2020)

Border Nation: A Story of Migration by Leah Cowan (Pluto Press, 2021, 160 pages)

From Banal Surveillance to Function Creep: Automated License Plate Recognition (ALPR) in Denmark by Gabriel Pereira and Christoph Raetzsch (from Surveillance & Society vol. 20, no. 3, pages 265-280, 2022)

Gordon Parks: Segregation Story. Expanded edition (Steidl, 2022, 208 pages)

No Pass Laws Here! Internal Border Controls and the Global ‘Hostile Environment’ by Kathryn Medien (from Sociology, 2022, vol. 57, issue 4, pages 940-956)

Hélène Amouzou review – spectral self-portraits of a soul in torment by Charlotte Jansen (from The Guardian, 2023)

When Wizz Air wrecked immigration stats by Tim Harford (from FT Weekend Magazine, 2023)

On Pothichoru: How the humble packed meal might foster a sense of egalitarianism by Deepa Bhasthi (This Is Mold, 2024)

Students’ futures still blighted by English test scandal by Nazek Ramadan of Migrant Voice (Letters to the Editor from The Guardian, 2024)

BONUS: Another book review!

In other news, I have recently written a review of Design Social Change.

Written by Dr. Lesley-Ann Noel, the book draws on her academic research, teaching experience, plus years of feminist and decolonial scholarship, resulting in a valuable guidebook for designers and researchers who are serious about striving towards equitable social change.

Read my review at the Design Research Society.

Gabriel Pereira, a Visiting Fellow at the London School of Economics, is currently researching the genealogy of algorithmic surveillance technology. His research has a particular focus on the history of Automatic Numberplate Recognition (ANPR) within the City of London, tracing its origin from the first use of ANPR in 1981 at the Dartford Tunnel (a system developed by former colonial police officers who then worked at the Home Office) to the emergence of contemporary intelligence-led policing.

Good to see Amouzou in the mix here. An apt visual metaphor indeed. Her exhibition at Autograph stayed with me. So well executed. As for Parks, well he was the master of his time whose relevance will extend beyond ours.

I learnt so much from this post. Thanks for signposting Daniel Mebarek’s map for the Photographers Green Book. Readers can listen to a chat I had with its founder Jay Simple here https://pod.link/1469562537/episode/4187e53a0c52cb3face405a3c6eda379