From a thirteenth-century Brazen Head to Secretaries of the Imperial Age — how voice assistants continue centuries-old cultural imaginations of voice command which enforce sociolinguistic discipline on marginalised dialects, rural and inner-city sociolects

🎟️ I will be speaking at UNPARSED — The World's Most Loved Conversational AI conference! My talk “Whose English gets to be default?” will critically examine why accent bias, gender stereotypes and nationality are all problematic factors in automated speech recognition technologies. It’s all taking place in London and online from Monday 17 — Wednesday 19 June. My talk is on Tuesday 18 June at 4:15pm.

🇸🇪 Hej Hej Sverige! I am also speaking at The Conference, Malmö which runs from Tuesday 27th — Thursday 29 August. My talk will be on day 2 as part of a session called “Rewilding Us”, where I will speak on imagining futures that decentre humans in design, in dialogue with Black Feminist and Indigenous knowledge traditions.

🔓 No paywall this month. Enjoy!

📚 You can buy any book in this newsletter from my store on Bookshop.org

Talking computers have captured our cultural and technological imaginations for decades. Spike Jonze in his 2013 film Her, depicts a near-future drama about a lonely writer who falls in love with his artificially intelligent operating system — a plot direction that both pre-figures and trails how smart assistants and chatbots have since evolved.1

Despite significant advances in how natural speech is understood by computers or phones, we are still bound to our keyboards. Speaking to a computer gives an illusion of total control, where the human can feel elated at being in charge of a subservient robot.

But what does it mean to speak to a machine or robota? To be understood, what kind of English needs to be spoken? — and by extension, whose English is excluded?

Commanding robota

Some of my favourite science fiction TV series of my teenage years featured intelligent computers that could understand speech.

In Quantum Leap, time-travelling scientist Dr. Sam Beckett is teleported into the bodies of other people from the recent twentieth-century American past. The show was not afraid to tackle civil rights, gender, and race relations in its episodes. As he inhabits these other bodies, he finds out how he must correct a historical wrong before he can Quantum Leap again — all in the hope that he will eventually return home to the present day and his own body. Throughout each episode, Sam is assisted by Al, his friend and mentor, whose interventions provide comic relief as he bickers with Ziggy, the handheld device that gives him predictive insights about imminent events through a symphony of bleeps and bloops.2

Talking computers and people who can speak to computers are fundamental to techno-optimist cultural ideals. The fascination with automata — from the legend of Friar Bacon’s Brazen Head in the thirteenth century to the chess playing Mechanical Turk in 1770 — our shared cultural histories of commanding robots underline how magical thinking and verbal control have been a persistent dream.

In the late twentieth century, as computers migrated from laboratories to homes and offices, they became tools of drudgery. Workers and students alike spent hour after hour hunched over keyboards. To turn speech into text was a labour-saving dream that continues to hold allure.

Voice assistants became a mass-market consumer product in 2011 when Apple launched Siri as part of iOS5. Apple has long pursued various concepts to imagine how voice-to-text interfaces might work— most famously with the Knowledge Navigator in 1987.

Keyboards and other mechanical input devices represented technology of a mechanical past. To use voice as a controlling mechanism gestures to a techno-optimistic future — one where a human speaks, and the machine — often feminised, always subservient — responds with alacrity.

Our cultural imagination shapes, and has been shaped, by how smart computing technologies have developed, but there are deeper socio-historical and political perspectives to consider.

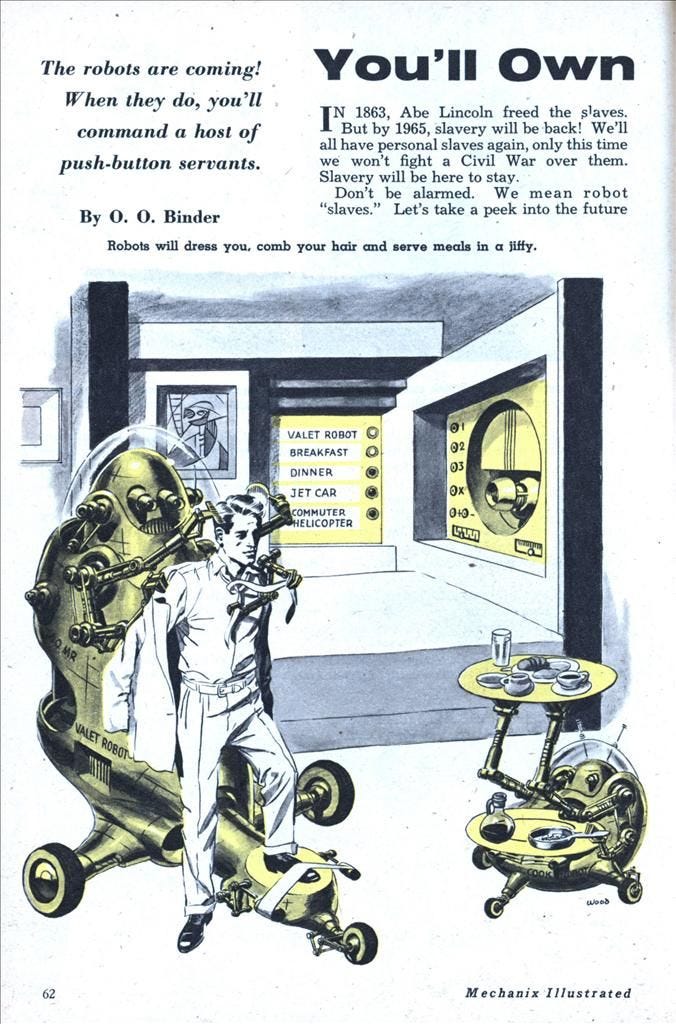

American robot concepts of the 1950s were often presented as entities that endured the drudgery of domestic labour. However, labour must be understood through a lens that is classed, racialised, and gendered. Ruha Benjamin, in her 2019 book Race After Technology, explains how the figure of the robot, or robota as its Czech root word directs, means “compulsory service”. In the figure of the robot, the human desire was always to have a servant that is ever-attentive and responsive to our demands.

We labour under the system of racial capitalism, which creates racialised and gendered difference — first, of the worker; next, of their worth and agency.

Mid-century American visions of robotic automation focused their attention on the domestic sphere — in a bid to automate perceived “low value” domestic labour out of existence: often, low or unpaid work carried out by women — immigrant and minority ethnic women in particular.3 Dr. Thao Phan in her journal article, “Amazon Echo and the Aesthetics of Whiteness” argues that Alexa, as a technological substitute for domestic labour, serves the continuing need for subservient labour while making invisible the problematic presence of the racialised domestic worker.

The visibility of domestic labourers, particularly those providing care, is tainted by a violent past of enslavement, economic inequality and geographic displacement. It is remarkable to see history repeat itself when we are presented with new types of smart robotic technology.

In the late eighteenth century, Thomas Jefferson dazzled his dinner guests at his country estate at Monticello. They defined Freedom for a New Nation, while being served meals from a dumbwaiter in the corner of the dining room. The forlorn presence of Jefferson’s enslaved kitchen brigade toiled silently out of sight to send up these dishes and fine wine, so the delicate sensibilities of Jefferson’s guests were spared the sight of the physical, sexual and emotional violence that permeated the estate’s operation:

“... the purpose of the dumbwaiter was to exclude Black voices and Black ears from the conversation above. The dumbwaiter, then, did not merely regulate the boundaries of a sphere that was reserved … for the public use of reason; it helped to produce that sphere by minimizing interference and distortion, and restricting transmission and communication in a manner that ontically differentiated master from slave.” — “Drawing the Color Line: Silence and Civilization from Jefferson to Mumford” from Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, pg. 66

From Monticello to Amazon Fresh — despite changing time, technology and geography — we see similar power and exploitation dynamics repeat. The magic of Just Walk Out™ technology claiming to be able to magically sense the items we take from its shelves, now revealing the prosaic reality that the whole charade operates with brigades of invisible (and low-paid) workers in India “annotating AI-generated and real shopping data to improve the Just Walk Out system.”

Who is the robot?

From the domestic robots of the 1950s to the modern voice interface, there is a logic that binds these superficially different technologies. The feminised voice of Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri, OpenAI’s Sky, and others suggest the persona of an efficient, professional secretary — a confidant who is always on hand to leap into action.

In their journal article “Alexa, Tell Me about Your Mother”, Jessa Lingel and Kate Crawford examine the feminisation of the secretary and how our modern voice assistants are technological reconstructions of this intimate relationship:

“…soft AI technologies typically default to a feminine identity, tapping into a complex history of the secretary as a capable, supportive, ever-ready, and feminized subordinate.” — Alexa, Tell Me about Your Mother

For much of history, a secretary held a position of great authority, being taken up by men — because they were always men — who were close confidants of high-ranking military officers or senior politicians. The role of the secretary became feminised as more women entered the workplace in twentieth-century Anglo-American and European societies. Despite this, the relationship between leader and secretary remained uniquely intimate. Today’s voice assistant continues this relationship, albeit one that is mediated by a technology platform.

“.. one of the key functions of the secretary, that of keeping secrets, is ultimately inverted. The data, and the patterns in the data, are being shared with a technology company… this information travels beyond workplace walls, into databases of tech companies to be listened to by contractors, leaked online, and potentially sold to data brokers.” — Alexa, Tell Me about Your Mother

A secretary is both subservient and powerful — they control access to the leader — overhearing private conversations and witnessing their leaders at their most vulnerable. Some of the men whom secretaries served became incapable of organising their days or functioning without their guiding hand.

To smooth over this troubling dynamic required a calm voice. Although the men were in charge, they also needed to be reassured that their functional impotency was not publicly visible. The secretary’s voice — human or machine — existed to soothe the male ego.

Whose English gets to be default?

When robots speak, whose voice do we hear? When we speak to our voice assistants, how must we sound to be understood? Are we conscious of the linguistic discipline — pronunciation, vocabulary, and sociolect — that invisibly defines vocal interactions between humans and computers?

“Every established or emerging norm needs to be interrogated — whether the taken-for-granted whiteness of humanoid robots, the ostensibly “accentless” normative speech of virtual assistants, the near invisibility of the human labor that makes so many of the ostensibly “automated” systems possible…” — Your Computer Is On Fire, pg. 4

The knotty issue of accent bias — perhaps, the last socially acceptable form of prejudice in Britain — is infused into how speech recognition technologies operate. There is a social and cultural tension at play, where acceptance of sociolects closely associated with working class and minority ethnic communities (such as Multicultural London English — a sociolect that has an outsize influence on the language of inner city urban and rural youth of all backgrounds) are functionally marginalised so they remain absent from training corpora that govern how automated speech recognition (ASR) technologies work.

“Choosing which types of English are supported is a decision not arrived at democratically, e.g. by the number of people who speak a dialect or sociolect, but rather by commercial priorities of the device manufacturers.” — Accent, and the Effects on an Individual When Misunderstood by a Voice Assistant, pg. 14

Our first reaction to address accent bias may be to argue for greater national and ethnic diversity in the people involved in the design of such technologies. But how can such diversities even begin to address the subtle layers of social and regional prejudice that uphold the suppression of Englishes most closely associated with working class, rural and minoritised ethnic communities — both in isolation and combination?

“A former Apple employee who noted that he was “not Black or Hispanic” described his experience on a team that was developing speech recognition for Siri… As they worked on different English dialects – Australian, Singaporean and Indian English — he asked his boss “What about African American English?” To this his boss responded: “Well, Apple products are for the premium market.” — Race After Technology, pg. 28

On the internet, we live and breathe whiteness. We could argue that our goal should be to achieve race and gender-neutral personas, but infused within each of these ideals are centuries of racial and gender oppression. The conventions of speech recognition are governed by respectability that signals intolerance of marginalised communities.

“… the internet should be understood as an enactment of whiteness through the interpretative flexibility of whiteness as information. By this, I mean that white folks’ communications, letters, and works of art are rarely understood as white; instead they become universal and are understood as “communication”, “literature” and “art” — Distributed Blackness, pg. 6

Racial difference is conditionally tolerated, so long as it sonically adheres to, and agrees to be governed by markers of respectability — sociolects, dialects and accents are convenient handles for weeding out undesirable aspects of ethnic, class or cultural difference. So how can we begin to reimagine these types of speech recognition technologies?

Art as liberatory research

Perhaps artistic research can help break some of these problematic ethnic, gender and cultural tropes. Untethered by corporate orthodoxy, metrics or strategic goals, a promising chance for imagining a more equitable future for how such technologies could work will surely emerge from an artist’s — rather than an agency’s — studio space.

Nadja Verena Marcin is one example of an artist who has experimented by creating a voice assistant called #SOPHYGRAY. From the intersectional feminist literature used to train its speech, to the way its responses develop after continued use — the user’s perspectives on talking to a chatbot defined by its relation to feminist literature could start to redraw our perception of what conversation with a computer means.

Feminist ideation starts by examining power, so challenging the centralising tendency of natural language processing technologies is an important first step. Our critical attention could also focus on subverting the problematic racial, gender and socioeconomic stereotypes infused into the White feminised personas that voice assistants often suggest — and perhaps even disrupt the cisgender binaries infused within the design altogether.

“The “presumed racelessness” of voice assistants and their supporting infrastructures erases and flattens the identities of those who do not, or can not conform for reasons of ethnicity, gender identity or expression, ability, nationality, and social background. Raceless imagined identities reflect the deeply entrenched formations of what we know a standard accent or standard user to be.” — Accent, and the Effects on an Individual When Misunderstood by a Voice Assistant, pg. 26

The secret sauce of any conversational AI system is in its data. So what alternative approaches can be used to wrest control of the training corpora? The languages captured in language corpora exclude many populations. And even within widely spoken languages such as English, regional accents and dialects are absent or poorly represented.

Despite my earlier complaints of marginalisation and exclusion, I simultaneously grapple with the discomfort of advocating for the expansion of data to build speech corpora trained on the voices of marginalised communities, when the economic and technological benefits flow towards the private technology corporations that own and build these systems.

There are other ways to build. Other futures are possible.

Masakhane (meaning “We build together” in isiZulu), is a community of African NLP researchers, data scientists, and developers working to capture some of the 2,000 plus African languages overlooked in speech recognition representation. Community-owned, ground-up attitudes have resonance, as they re-enfranchise historically marginalised groups. In Aotearoa — New Zealand, Te-Hiku Media has taken an approach of collecting and building Maori language corpora while also retaining its ownership rights, so that the financial and intellectual benefits remain with the communities on whose voices and labour the system relies.

“The construction of the voice assistant’s sociophonetic identity on national grounds alone — while understandable for linguistic, navigational and configuration purposes — echoes histories of social exclusion.” — Accent, and the Effects on an Individual When Misunderstood by a Voice Assistant, pg. 57

And finally, what about nationality? We negotiate the use and definition of digital synthetic voices in our smart assistants through the politically constructed edifice of the nation-state, but as we have witnessed — what does a nation even mean for someone who speaks British English? From which region, city or county do they originate? How have their life experience, migratory history, and social or cultural grouping, contributed to the formation of their speech?

“… I no longer see the shame and paranoia of racialised misrecognition, rather I see these aberrations as gifts, as a reminder that the fullness of racialised life can never be captured, never be frozen and transcribed inside of racist domains of transcription. It’s a reminder that we don’t need to look to a failing system and ask to be granted legitimacy. On the contrary, our legitimacy is in our excess, our failure to align with homogenous technical standard. It allows us to look at that system and say ‘A machine is not the arbiter of my humanity’” — Thao Phan, performance lecture “Listening to Misrecognition” (41:41)

There are many ways to reimagine automated speech recognition technologies — especially as Amazon continues to lose interest and money in propping up Alexa. Answering these questions may frustrate the solution-driven logic under which we labour. We may have to accept that our immediate concern should be to disruptively ideate — embracing the discomfort of not knowing where these new questions will take us.

Explore further

Listen

Transcripts are available for Rebecca Woods on Large Language Models, Language and Meaning, and How Children Learn Languages.

Watch

In this performance lecture, Dr. Thao Phan explores the tension existing between misrecognition and the precision of categorisation lying under the surface of automatic speech recognition technologies. Informed by critical feminist and race studies, her personal and empirical research, we are shown a novel way of thinking about how such technologies not only shape how we speak but also enforces how not to speak.

Dorothy R. Santos presents a brief and thought-provoking lecture titled “Sonic Futures” inspired by the work of three artists who question our notions of “good” English, conversation dynamics, and our relation to sonic environments — drawing insights that feed into new ways of defining Conversational AI.

Resources

Important research projects about accent bias in Britain have been in progress for a number of years. Accent Bias Britain examines its effect in the workplace and seeks to define methods for combatting these biases. Speaking Of Prejudice is a research project led by Dr. Robert McKenzie that examines implicit and self-reported attitudes towards accents spoken in Northern and Southern England.

Dark Matters by Johann Diedrick. Thank you to Ploipailin Flynn of AIxDesign for drawing my attention to this. AIxDesign is a global collective of designers, artists and researchers working to “democratize AI literacy and critical discourse, practice critical & creative thinking, and research and prototype new ways of being in relation to AI and technology.” If you like what I write about and also think between disciplines, click through to see what they are up to.

Feminist Internet is a feminist design and research collective that prolifically ideates to disrupt stereotypes and exclusion in the technology industry. From Syb, their queer voice AI, to designing an ecological or feminist Alexa (supported by the UAL Creative Computing Institute in London), their projects present thought-provoking alternative modes of speaking to computers.

There are a growing number of community-led, open-source and African-centred initiatives that are building speech corpora for African languages. GhanaNLP, Lelapa.AI and Masakhane are just a few promising examples in progress.

Read

Amazon Echo and the Aesthetics of Whiteness by Thao Phan (from Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, vol. 5, issue 1, pages 1-38, 2019)

Because Internet: Understanding how language is changing by Gretchen McCulloch (Vintage, 2019, 336 pages)

‘Like’ isn’t a lazy linguistic filler – the English language snobs need to, like, pipe down by Rebecca Woods (from The Conversation, 2019)

Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code by Ruha Benjamin (Polity, 2019, 285 pages)

”Alexa, Tell Me about Your Mother”: The History of the Secretary and the End of Secrecy by Jessa Lingel and Kate Crawford (from Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, vol. 6, issue 1, pages 1-25, 2020)

The Computer’s Voice: From Star Trek to Siri by Liz W. Faber (University of Minnesota Press, 2020, 256 pages)

Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures by André Brock (New York University Press, 2020, 271 pages; also available as a free eBook under Open Access)

Accent, and the Effects on an Individual When Misunderstood by a Voice Assistant by Michael Kibedi. MSc Human-Computer Interaction Design dissertation (unpublished manuscript), submitted December 2021 at City, University of London. Academic supervisor: Dr. Alex Taylor

AI Assistants (The MIT Press Essential Knowledge series) by Roberto Pieraccini (MIT Press, 2021, 288 pages)

Conversations with Things: UX Design for Chat and Voice by Diana Deibel and Rebecca Evanhoe (Rosenfeld Media, 2021, 320 pages)

Māori are trying to save their language from Big Tech by Donavyn Coffey (WIRED, 2021)

Oh my days: linguists lament slang ban in London school by Robert Booth (from The Guardian, 2021)

Your Computer Is On Fire edited by Thomas Mullaney, Benjamin Peters, Mar Hicks and Kavita Philip (MIT Press, 2021, 376 pages)

Bias in Automatic Speech Recognition: The Case of African American Language by Joshua L. Martin and Kelly Elizabeth Wright (Applied Linguistics, vol. 44, Issue 4, August 2023, Pages 613–630)

The Smart Wife: Why Siri, Alexa, and Other Smart Home Devices Need a Feminist Reboot by Yolande Strengers and Jenny Kennedy (MIT Press, 2023, 320 pages)

Towards Intersectional CUI Design Approaches for African American English Speakers with Dysfuencies by Aaleyah Lewis, Jay L. Cunningham, Orevaoghene Ahia, and James Fogarty (University of Washington, 2023)

Who makes AI? Gender and portrayals of AI scientists in popular film, 1920–2020 by Stephen Cave, Kanta Dihal, Eleanor Drage, and Kerry McInerney (from Public Understanding of Science, vol. 32, issue 6, 2023, pages 745-760)

Can We Create an Intersectional AI? by Ariana Dongus (HyperAllergic, 2024)

Disappearing tongues: the endangered language crisis by Ross Perlin (The Guardian, 2024)

Experience: ‘I woke up with a Welsh accent’ by Zoe Coles (The Guardian, 2024)

Isolated for six months, scientists in Antarctica began to develop their own accent by Richard Gray (BBC Future, 2024)

Soon after I put the finishing touches to this essay last month, Scarlett Johansson hit the headlines after criticising OpenAI for using a voice eerily similar to her own in Sky — their latest Chat-GPT powered product. According to the Financial Times, Johansson said OpenAI CEO Sam Altman asked her to voice their upcoming ChatGPT release to “bridge the gap between tech companies and creatives and help consumers to feel comfortable with the seismic shift concerning humans and AI.” She added, “[Sam Altman] said he felt my voice would be comforting to people.” [Emphasis mine] — all of which is a useful reminder of how patriarchal design culture veers back to problematic gender stereotypes. OpenAI couldn’t have done this more spectacularly by choosing the voice of Her!

Now I think of it, I’m not so sure. Did Ziggy really understand speech? Or was Al repeating Ziggy’s beeps as a dramatic device? I’ll have to rewatch some old episodes… 🧐

In The Smart Wife: Why Siri, Alexa, and Other Smart Home Devices Need a Feminist Reboot (MIT Press, 2021), the co-authors Yolande Strengers and Jenny Kennedy add the concept of digital housekeeping (“integrating, maintaining, and monitoring multiple devices and systems, troubleshooting issues, and upgrading, updating, or repairing software and hardware”, pg. 43), and how much of this work is done by men — further complicating the ways we assess the domestic labour landscape. Our view is likely distorted due to how the maintenance of the digital elides “traditional” domestic labour surveys.

This is fantastic, Michael. I shall definitely be sharing this with LTUX Brighton co-organisers as there is lots to think about here with regard to our FemCoded discussion event coming up in September.