Meshwork by Merve Mepa

Connecting the structural logics of weaving to the complex digital infrastructures of today

A retrospective review of an Istanbul conceptual art installation which asks searching questions about the interconnectedness of weaving and the inscrutability of technological infrastructures, before we swerve to find parallel connections in the ethnomathmetical cultural memory of Afro hair braiding

📚 You can buy books mentioned in this newsletter from my page on Bookshop.org

⚡ I will be speaking at The Spaces Between, a two-day creative festival by Where Are The Black Designers? The event takes place on Saturday 30 and Sunday 31 August at EartH in Dalston, London. I will be speaking on Saturday. This is a conference festival with a difference: there will be talks, creative workshops, an after-hours club, jazz nights, and quiet places to recharge during the day. Tickets are still available: Full Weekend, Day 1, or Day 2. Follow WATBD on Instagram or LinkedIn for all new announcements. 🖤

Meshwork

Picture the scene. A sparse room in the basement of what was once the headquarters of the Imperial Ottoman Bank in Istanbul. The building has since been transformed into SALT Galata — a dual-site library, research, and exhibition space. Earlier in the summer, SALT Galata was home to Meshwork — the newest installation by the Turkish conceptual artist, Merve Mepa.

A tessellated assembly of tiles rises to form an island in the middle of the floor, suspended using a method familiar to anyone who has maintained cables in a data centre. Strip lights fill the room with a blue-grey hue.

In the depths of this former bank, it is as if the building’s inner pulse has been revealed. A network of pipes suspended from the ceiling, suddenly cornering this way and that as if they are being impelled by invisible force fields before cascading down towards half a dozen screens and microcontrollers suspended mid-air.

This is Meshwork. When I interviewed its creator Merve Mepa in July, I was interested to get beneath the surface of this installation to learn how she brought this apparition into being.

Meshwork’s industrial sheen could be mistaken for part of the building’s service infrastructure — that rare glimpse you get when an engineer momentarily leaves a door ajar, exposing diagnostic LEDs blinking in a dim server room.

First-time visitors will misinterpret Meshwork — an anticipated mistake the artist invites. Merve was keen to elucidate to me how she intended this installation to occupy its space:

“The exhibition space at SALT — located one floor below ground level — immediately resonated with the core idea of Meshwork, which deals with invisible infrastructures. The space felt like a hidden layer of the building, much like how certain systems or networks are hidden in plain sight… Because of its location, there’s already a deep hum in the room from the building’s ventilation, sewage, and other infrastructural systems…

… that’s why I didn’t want to treat Meshwork as a discrete art object suspended in a room. Instead, I decided to rebuild a structure that feels like part of the space itself. The metal pipes blend with the architecture, almost camouflaged. In fact, some visitors thought the installation was part of the building’s original infrastructure, which, for me, means the work succeeded in dissolving the boundary between artwork and environment…

… I wanted to preserve that natural hum in the building, but also expand on it, so I layered it with low-frequency drones and industrial factory sounds, which also echo the mechanical rhythm of a weaving loom. For me, the entire installation — with its grids and lines — functions like a large-scale loom stretched across the space. The sound was composed in collaboration with Alp Tuğan, who helped bring this sonic idea to life.” — Merve Mepa interviewed by Michael Kibedi (First & Fifteenth), 10 July 2025

Bringing Meshwork to life

Meshwork is a multi-layered work emerging from Mepa’s research-led practice on the cultural memory of weaving. While other researchers choose to focus on aesthetic or decorative features, Mepa explores these materials from an ethnomathematical perspective to unravel how the computational logics of weaving connect to the cultural memories of weavers, and how the porous boundaries of these environments are metaphorically reminiscent of the threads that constitute the digital infrastructures surrounding us today.

When we consider technological infrastructures governing our lives, Mepa urges us to pay equal attention to the invisible elements of these infrastructures, because they often obscure sociotechnical factors that contradict the mental models we hold towards the internet and the way our digital existence is bound.

Access to the internet is not democratised. Internet connectivity materially echoes geopolitical tensions while crystallising past colonial pathways. The cloud is not immaterial. Calculative technologies are not stable foundations for preserving cultural memories.

In her TEXT explaining Meshwork’s provenance, Mepa explains how the perceivable technological artefacts making up Meshwork are symbolic of the immersive interest she has with ancient weaving technologies:

“For about three years, I have been studying the history and cultural memory impacts of handcraft practices, particularly weaving, as well as networks and the effects of contemporary hardware and software technologies. I place ‘thread’ at the center of this study. This is because the concept of ‘thread’ encompasses many meanings related to the recording of environment, technology, and memory.” — TEXT by Merve Mepa

Merve expanded on this theme when we spoke. She was keen to clarify why she continues to be unsettled by the duality of these seemingly unconnected architectures. It is the invisibility of technological infrastructures and the power embodied in these centralising systems that gather so much from us, from our planet; how our grasp of cultural memories of handicrafts maintained within small communities fades from view. It is our waning capability to scrutinise their sociotechnical effects as the invisibility of such expansive technological infrastructures are both materially and linguistically obscured:

“Today’s systems may appear seamless and unified but they are governed by hidden infrastructures that shape not only how we move through the world, but how we understand it. Meshwork was directly inspired by these invisible yet powerful systems: algorithms, protocols, control systems, and the structural logic of weaving itself.” — Merve Mepa interviewed by Michael Kibedi (First & Fifteenth), 10 July 2025

There are archival interests submerged within Mepa’s research. Her inquiry typically begins with contemplating ancient looms and the computational methods that control such machines. As we delve through the material she has amassed, we realise that the production of carpets in Türkiye finds parallels in textile production across many cultures — each using algorithmic instruction to texturally capture cultural, spiritual, and personal glimpses of the weavers at the helm.

There are archaeological interests embedded in Mepa’s research. As she traces the dawn of the modern computer age, we follow threads from the industrialisation of textile manufacture to the creation of Babbage’s first calculating machine. Mepa explained last year, in conversation with Maya Kil for MADE IN BED, that: “The transmission of knowledge was not [always] in the hands of a single control mechanism. Method and knowledge were disseminated between communities through forms of transmission. This is very important for the recording of social memory” — a reminder that our arrival in the Modern age was predicated on the polarisation of knowledge and the imposed hierarchies that stratified our ways of knowing.

There is a poetic turn embellishing Mepa’s research. To identify thematic resonance across disciplines requires an inquisitive outlook that is unafraid to confront the imaginative constraints of a technology industry that proclaims disruption but refuses to countenance the reconfiguration of its extractive foundations.

When Merve spoke to me, she told me: “I’m not focused on the final outcome at the beginning of a project — instead, I try to open up a subject as much as possible, digging deeper into its layers... [Eventually] the piece chooses the form it needs.” As an artist-researcher in tune with the rhythmic clatter of these looms, we witness how the rhythm needed to orchestrate a weaving operation is poetically articulated by the material objects across her installations. Paying attention to the rhythms of the ecosystems surrounding us is a tacit admission that the disembodied rationality of the past has served us poorly. We are striving towards what Ari Melenciano says is a better recognition of “complex, adaptive, emotionally and culturally encoded systems.”

Inspiration

Merve’s central concern began with a childhood interest in carpet weaving. She explains to me how this fascination began:

“My father was a carpet dealer and a carpet designer. When I was a child, I was always between looms. I tried to weave, but I couldn't. I'm very familiar with carpeting and its design. All these symbols: I know all the history, I know all the weaver women, but I couldn't weave because I didn't have the desire. So, I asked myself, what should I use instead of this material? So then I started to try to understand the logic behind it. I said, ‘OK, this is a language’. I did my research on its logic — it’s all about zeros and ones but it means something at the same time and how it was transformed during history. I thought, maybe I should go deep into this.” — Merve Mepa interviewed by Michael Kibedi (First & Fifteenth), 10 July 2025

Beyond the multicoloured threads and intricate patterns, Merve has since gained a PhD in the ethnomathematics and gender politics of textiles, weaving, and artistic method — interests which have become all-consuming.

The parallels she sees between the handicrafts of the past — machines governed by precise mathematical control — are mirrored in the networked computational systems that continue to surround and evade our gaze today.

While her artistic practice ostensibly examines the interplay of software and people, it is through her poetic yet scientific modes of inquiry that her work traverses formats as varied as screen, Jacquard loom punch cards, electronic circuit boards, and even a dedicated GitHub repository.

Look closer, and the expressiveness of each textural pattern produced by these hand-guided machines comes into focus. Further contemplation of this handiwork directs us to critically assess the gender and power dynamics of how such labour is organised in mechanised, tightly-controlled environments that appear to strip away the affordances of individual expression.

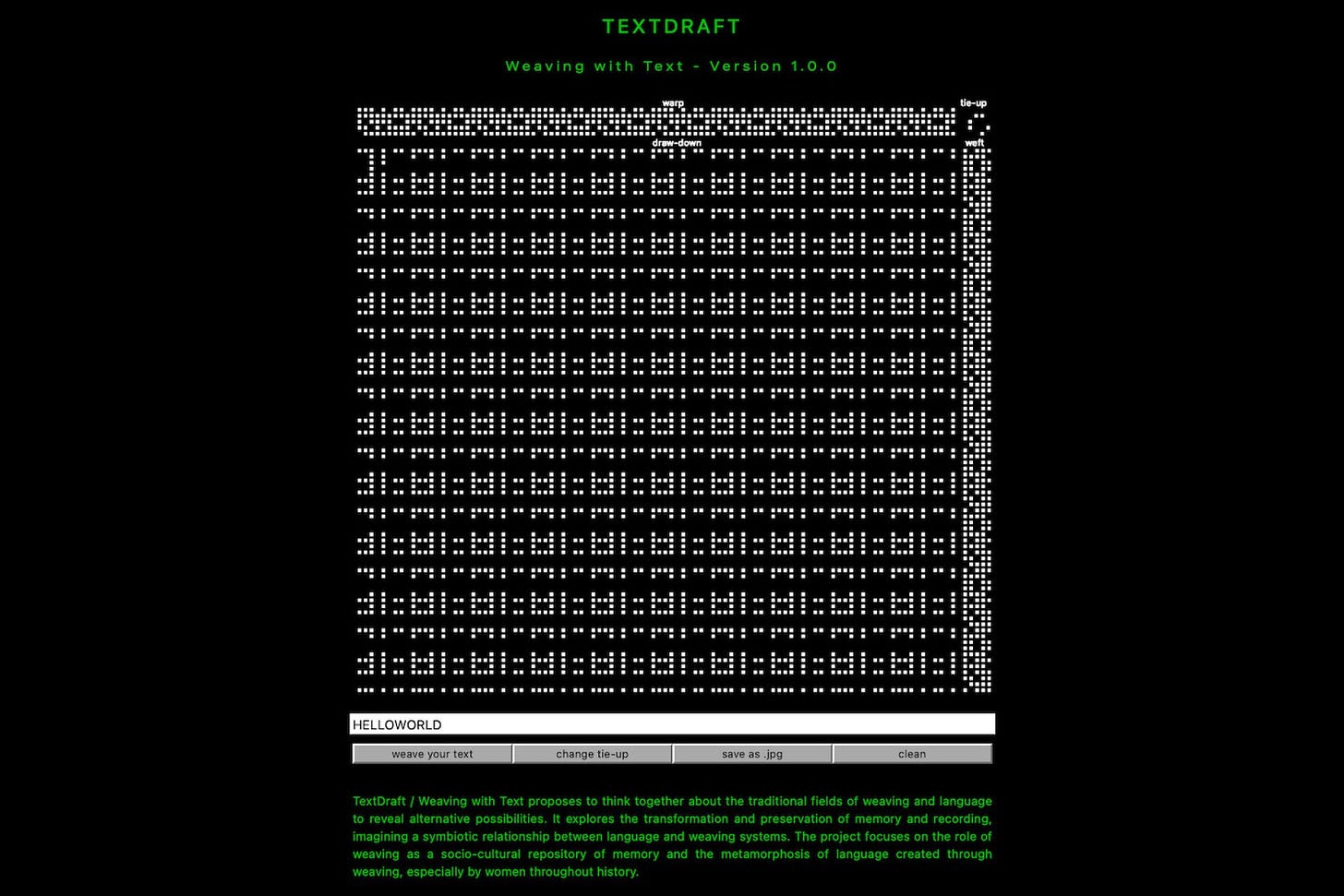

Explaining TextDraft, Mepa was clear that she does not want us to be passive bystanders:

“I want people to use it! It's so simple. I had the idea — not for recreating the same algorithm [so it can be] sold to an institution — I wanted some people, a few people, to see and reuse it. [In the second version] TextDraft v1.0.1, you can save it, you can change the pattern — it's reusable. I think open source culture is really important for these kind of concepts like collective, historical handicrafts.” — Merve Mepa interviewed by First & Fifteenth, 10 July 2025

For those of us steeped in internet subculture, the visual language of a project like TextDraft 1.0.0 is recognisable. White or green text on a black background recalls the early PC era of command prompts. For the extremely online, coding is a fantastical representation of fictional technological futures, despite the collective amnesia we have of coding’s feminised past.

Before the PC age, coding was deftly executed on looms. TextDraft 1.0.0, despite its ingrained culturally situated trope — subverted to great effect by Mepa — bridges a connection between the encoding of fabric and the weaving of text. We are furnished with an experimental digital loom. Mepa asks us to become involved, to play, and make ourselves known through code.

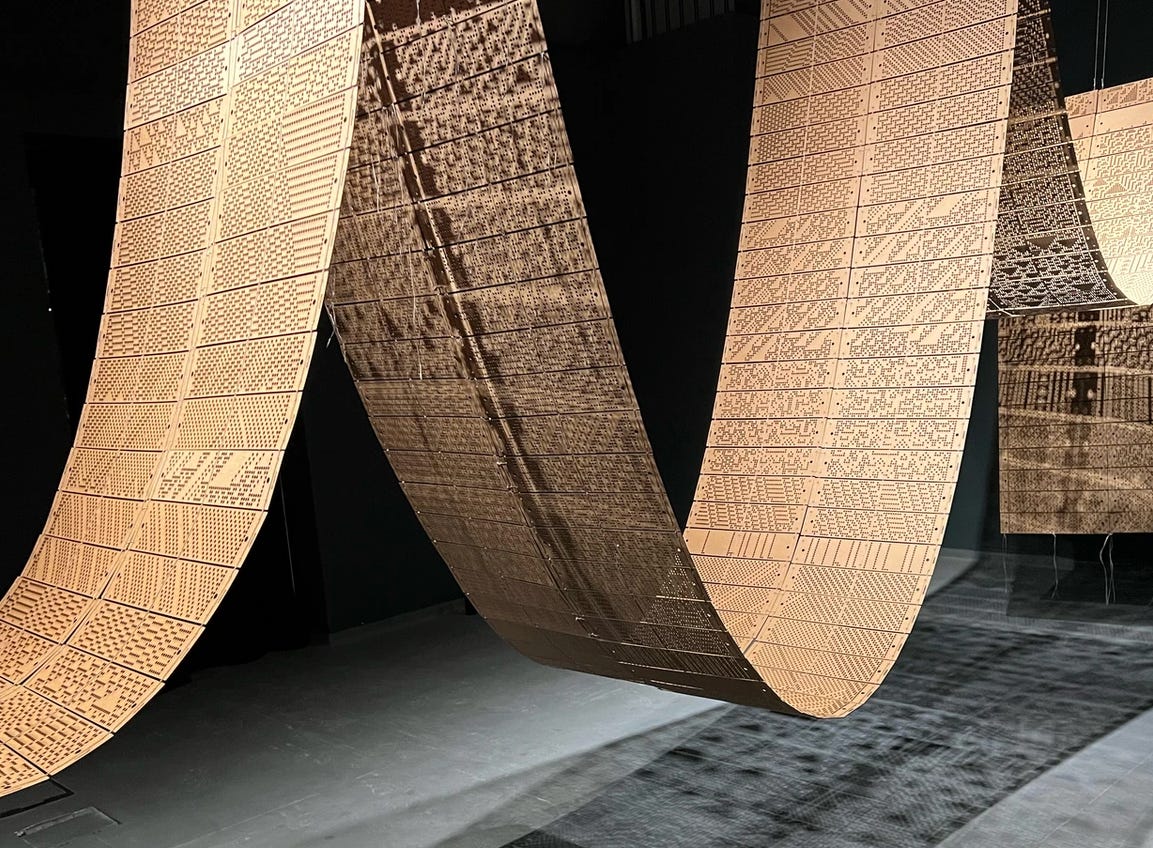

In N/A-A, Mepa turns our attention to the control mechanisms of the Jacquard loom. Named after Joseph Marie Jacquard, these looms opened new possibilities for creating intricately patterned brocades. Cards with arrays of punched holes feed streams of commands to the machine’s head to control the weaving of individual threads. Jacquard’s loom is widely recognised to have influenced Charles Babbage’s first Analytical Engine — a precursor to our modern computer.

The rigidity of the loom represents a mechanised operation that eliminates avenues for individual expressiveness; however, by coding through the rigidity of the machine’s affordances, such curtailments can be breached. A worker can name draft to make themselves known in their cloth — a codified manipulation of a pattern to pictorially represent a sequence of letters.

Viewed through a sociocultural lens, N/A-A is a rebuttal of Enlightenment ideals that are forever in pursuit of total control of its natural environment, of the raw materials extracted in service to manufacture, and of the workers subject to the demands of a never-resting machine. In her accompanying artist’s statement, she explains that:

“… both the human being and the machine become elements of a cybernetic system, a system of control and of communication. Zeros and ones are used as a means of recording memory and producing difference in both weaving and computer technology... This is what led Ada Lovelace, considered the first programmer [realised]: that the punched cards used in Jacquard looms were a means of recording memory and data: The possibility of acting without central control, an agency that does not require any kind of subject position.”

Despite being subservient to the rhythm of a machine that can not be overruled, there are ways a human’s relation to the machine can be rebalanced. Each punch card — encoded to produce a design at a prefigured speed — also represents an artefact of shared memory. The knowledge of how to weave is captured in these memory cards, passed down through space and across time.

So, where else can we detect ethnomathematical evidence that preserves shared cultural memories? Does their produce always have to be constrained to what a machine can produce?

Braiding and Infinity

Ethnomathematics are a gateway bridging logic and control on one side, with the communication of cultural memory and knowledge on the other. Beware: if we become fixated on the material, its message can be missed.

Infinity was once considered a dangerous idea. The gravity of its meaning is diluted because we have contorted its meaning to refer to an excess of time or distance.

From the Renaissance to the early age of European Colonial Expansion, infinity was considered destabilising to the foundation of mathematics, possibly unsettling the Divine; at least, until George Cantor coherently theorised its presence during the late 19th century.

In Don’t Touch My Hair, Emma Dabiri recounts the astonishment of early European colonisers when they landed on the coasts of West Africa. Aside from the orderly societies they found, it was the gravity-defying and mathematically ornate braided hairstyles that astounded. To observe a people whose heads were adorned with spiralling fractals was to witness an embodiment of a philosophical concept that, in Europe at least, was too dangerous to contemplate.

For the colonial project to work, it must convince us that the colonised are less-than-human; that they were incapable of advanced thought, that they lacked the foresight to master complex technologies. But the colonising invaders could not see past the fractals adorning the heads of those whom they sought to dominate: By becoming fixated on the material, the message was missed.

“Flying over an African village, you can see the recursive geometry of African fractals in their architecture: circles of circles, rectangles within rectangles, and other “self-similar” structures. These fractal patterns also appear in their textiles, carvings, paintings, ironwork and more. Other kinds of algorithms underlie the repeating sequences of bent wood arcs that make up Native American wigwams, canoes and cradles. Even henna tattoos demonstrate the interactions among computation, nature and culture.” — Heritage algorithms combine the rigors of science with the infinite possibilities of art and design

Fractals occur throughout nature. Their recursive patterns are evident in our bodies — our brains and lungs — and are expressed in the weaving of our Afro hair. Fractals braiding tells the story of a people in tune with the rhythmic existence of the natural world. Fractal braiding testifies to the ways ancient communities have communed with the spiralling geometries of clouds, leaves, and seashells — a mirror of how its mark can repeat over and over again.

From Kente cloth, to ancient African architecture, to the braids spiralling across our scalp — these ethnomathematical traces testify to an embodied application of creative technology — a point picked up by Emma Dabiri in Don’t Touch My Hair where she writes:

“Fractals are the shape of the universe, patterns that repeat themselves at many scales. In addition to our organs, fractal shapes make up the world around us: trees, rivers, coastlines, mountains, clouds, seashells, hurricanes are all fractal in design. Our lungs, our circulatory system, even our brain, all are fractal structures. We are fractal.” — Don’t Touch My Hair, pg. 224

The meaning of fractal braiding stretches back centuries with roots that are embedded far deeper than our scalps. Braiding portrays infinity as an embodied form of cultural memory, spatially and temporally preserved, orally communicated and algorithmically shaped.

This is where I see the connection with Mepa’s poetic sociotechnical concern. To look beneath the surface of the weave, we can also reappraise our perception of Afro braiding to see beyond the aesthetic.

Recursive tracks evident in braiding styles testify to a mastery of technology — in stark contrast to the modern extractive interpretation of this word — a stylistic reverberation of one being in close dialogue with the ethnomathematic origins of existence: a human that has an interdependent existence with the planets, and is cognisant of the geometry of the land, and the mathematical precision governing the inner working of our bodies.

What I have taken away from Merve Mepa’s work, and the parallels evident in textural and woven technologies of cultural memory — emerging row by row from a loom, or inch by inch in a set of braids — are technological infrastructures that are both expansive and discrete.

Their parallel presence facilitates the flow of information — from the cultural memory of the textile, to ancient patterns tied within a braid — and they speak to the tensions existing in how digital cultures persist across internet infrastructures.

Our cultures are fluid, bound by the technologies giving them form, but these disparate artefacts can not curtail the imaginations of those who seek to express themselves through and beyond these paths.

Thanks

🫂 My deepest thanks to Merve Mepa — for your generosity and time; for sharing your private research, photos, notes and other resources; for taking time to speak to me at length; for responding to my emails over the past few weeks!

Meshwork credits

Meshwork (2025) was exhibited at SALT Galata in Istanbul from 28 May – 14 June 2025.

Media: Steel pipes, floor rises, screens, microcontrollers, custom electronics and ceramics.

Merve Mepa provides the following credits and thanks those who supported the delivery of this installation:

Sound Design and Technical Support: Alp Tuğan

Acknowledgements: Arzu Altincelik, Burak Ayazoglu, Omer Karabuya, Yagmur Irfan, Zachary Tong

Merve Mepa was supported by the Artistic Production Fund of Salt and the BBVA Foundation.

Disclosure

I have not been paid nor have I received any other benefit to write this article, either from SALT Galata, or its commercial and cultural partners. Non-attributed opinions and reflections expressed in this essay are my own.

Explore further

Merve has created a project page for Meshwork where you can find the TEXT I referenced extensively, as well as her library of readings and resources she gathered during her research.

Merve’s research-led art practice does not fit into a neatly pre-packaged category, which is what principally drew me to her work. For this reason the podcasts and literature I have collected may not appear to address Meshwork directly, but listen closely and you find they contain thematic echoes of Merve’s interests — the entanglement and fluidity of complex systems, computational logics captured in seemingly unrelated infrastructures, the historical and contemporary position of threads both as physical artefact and metaphorical representations of communicative traces.

Listen

A seemingly insignificant design decision — to standardise a packaging unit — is agreed, and its effects reverberate around the world. Ports have been rebuilt as a result of this decision, and supply chains have been rerouted. In Son[i]a #377. Charmaine Chua from the Radio Web MACBA podcast, a logistics researcher, discusses containerised global shipping and asks what economies in the Global South would look like if they could be untethered from an infrastructural reliance on the Global North. I referenced this interview in my review of Systems Ultra by Georgina Voss, and I repeat it here because it ties so closely to the research approaches that Merve Mepa uses. We are reminded that systems, aside from their material properties, have a politics. This podcast is not published on Spotify, so you may be able to find it on other podcast platforms, or you can stream directly from MACBA’s website. Published 18 July 2023, lasting 1 hour 46 minutes.

Transcripts are available for Geographical Imaginations, Needlework and History's Hidden Technologies with Isabella Rosner.

Also, take a look at…

Fabricating Adjacency is an art research project that explores the relationship between the textile company Vorarlberg in the Western region of Austria and West Africa. Since the 1960s, textile companies in this area have specialised in manufacturing lace and polished damask, which is popular in Nigeria, Ghana and Senegal. Connecting threads across oceans, the core team of Anette Baldauf, Susanna Delali Nuwordu, Moira Hille, Sasha Huber, Janine Jembere, Abiona Esther Ojo, Jumoke Sanwo, Mariama Sow, and Milou Gabriel combine their various expertise to expose the colonial histories embedded and obscured within these fabrics.

Watch

While this essay and exploration has been concerned with the metaphorical and literal threads that connect textiles to digital infrastructures, the artist Tabita Rezaire takes up a thematically resonant concern by plumbing the depths of our oceans. Contending with past and future, the waters of the Atlantic are a site of trauma and spiritual meaning — in Deep Down Tidal (2017), Rezaire illustrates how the coloniality of internet submarine cables are tightly bound and inseparable.

Read

J.D.'Okhai Ojeikere: Photographs edited by André Magnin (Scalo, 2000, 158 pages) — this book is out of print. Try your luck on eBay or a specialist rare art book seller like Climax. In London, you can freely access this book for reference consultation at the Stuart Hall Library at Iniva, or (by advance request) at the British Library.

Deep Carbon by Joana Moll (Research Values, 2018)

The Secret Lives of Colour by Kassia St. Clair (John Murray Press, 2018, 328 pages)

Don’t Touch My Hair by Emma Dabiri (Penguin, 2019, 247 pages)

Living Rooms by Sam Johnson-Schlee (Peninsula Press, 2022, 160 pages)

Server Manifesto: Data Center Architecture and the Future of Democracy by Niklaas Maak (Hatje Cantz, 2022, 112 pages)

On Domain Naming by Chia Amisola (Ambient Institute, 2022?)

Aeropolis: Queering Air in Toxicpolluted Worlds by Nerea Calvillo (Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2023, 285 pages)

From cyber to physical space: the concentration of digital and data power by tech companies by Sasha Moriniere (open data institute, 2023)

Maya Kil in Conversation with Artist Merve Mepa (MADE IN BED, 2024)

Systems Ultra: Making Sense of Technology in a Complex World by Georgina Voss (Verso, 2024, 224 pages)

Culture is the Cybernetics of Consciousness by Ari Melenciano (2025)

The Confiscation of Digital Memory by Kaloyan Kolev (Are.na Editorial, 2025)

Marcus du Sautoy and David Darling on maths, music and great art by Clive Cookson (FT Life & Arts, 2025)

Other Networks: A Radical Technology Sourcebook by Lori Emerson (Anthology Editions, 2025, 220 pages)

The Reenchanted World: On finding mystery in the digital age by Karl Ove Knausgaard; translated by Olivia Lasky and Damion Searls (Harper’s Magazine, 2025)

What Is a Website Good For? by Omayeli Arenyeka (Are.na Editorial, 2025)