How death is overlooked in digital design, raising further questions about our digital selves, data preservation and online memorials

More than half of adults in the UK have not made a will.

Estate planning is an uncomfortable reminder of our mortality, preventing us from confronting how and where our possessions will be distributed, and more importantly, to whom.

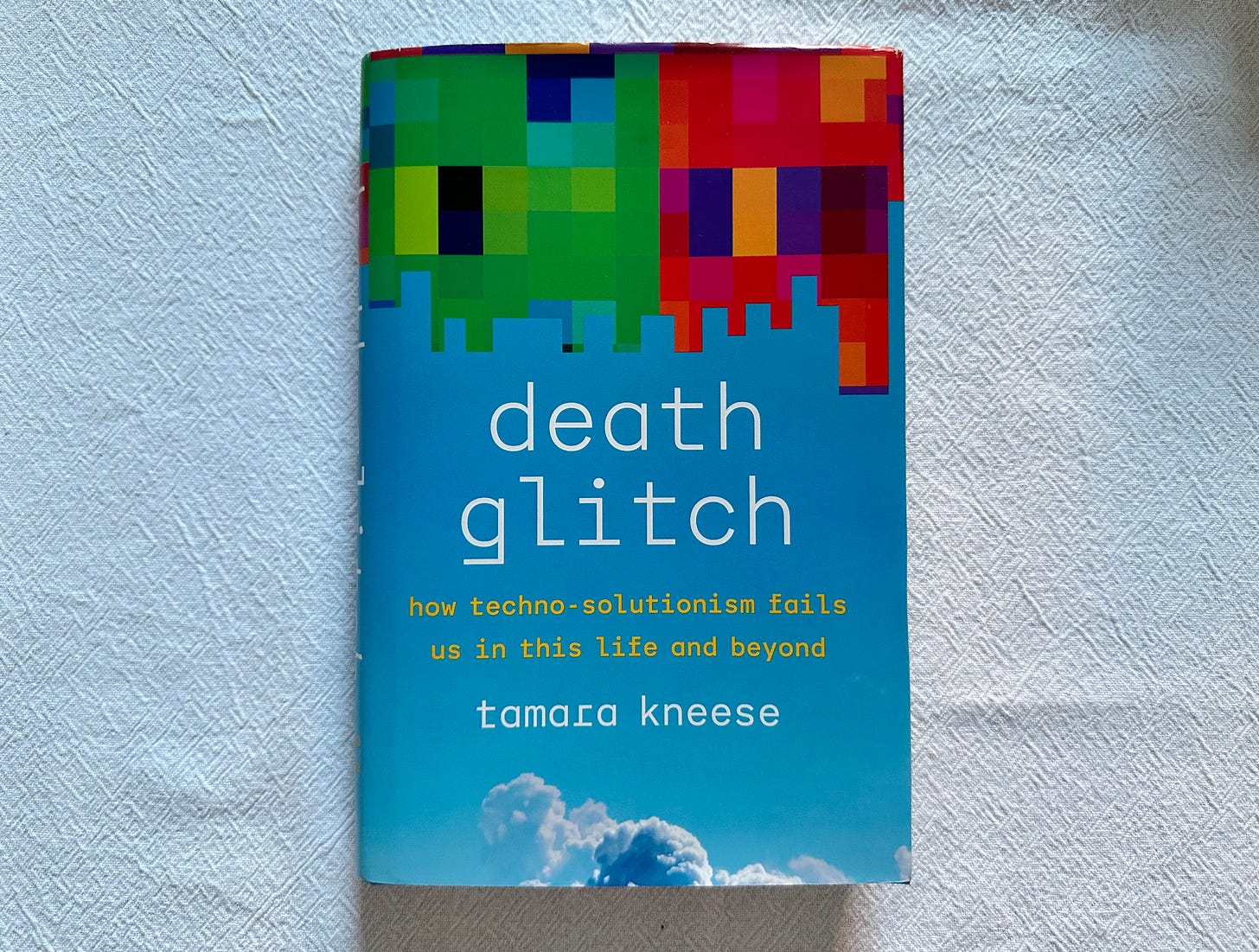

In Death Glitch, Tamara Kneese makes an important contribution to the field of socio-technical research by discussing how our mortality is overlooked or, in many cases, ignored in the design of digital platforms, services, and products. In doing so, we are invited to consider many important questions concerning the existence, maintenance and preservation of our data after we die.

Design for self

Commercial digital products and services are acquisitive by nature. The need for monetisation governs what data is and how it is structured. Investment is awarded on the expectation of continued, exponential growth. As a result, Design responds with methods that are biased towards acquisition — of more users, then of their data — resulting in services that are poorly equipped for responding to the social realities of when people die and how they are memorialised.

We think of our data, such as those represented in a social media profile, as individual work. Tamara Kneese argues that they are in fact “communicative traces”. Our digital selves are the results of multidirectional relationships existing between people and across platforms, with artefacts — images, messages, reactions — representing different facets of our personalities across time. Such traces can only exist within carefully calibrated technical architectures, code and managed storage.

In death, the “glitch” occurs when the networked labour maintaining these digital selves is suddenly made visible, or the gaps in the product or service design are unceremoniously exposed.

If a death glitch occurs because of an automated algorithm, such as an anniversary reminder, it can be haunting, or at other times traumatic — even distressing.

A death glitch forces us to confront questions that have not been considered by those responsible for the product or service design: Should a person be digitally memorialised? If so, how? For whom should digital selves be preserved when the social reality is that people present different versions of themselves across multiple platforms?

“Blogging and other social media platforms are designed with single users or authors in mind; however, dying and death create glitches that expose the collaborative nature of digital production. Sometimes these glitches manifest in lost domain names or unchecked accounts; other times algorithms make it feel as if the dead are trying to make contact from beyond the grave.” — Death Glitch, pg. 95

I am reminded of research by digital media scholar Francesca Sobande describing how the ability to opt out of the collective online memory is a choice that is not equally afforded, resulting in harms that can be specifically harmful towards the Black people who use such digital products and services.

“Media content depicting the everyday lives of Black people and their experiences of pain, even, death, is often spectacularized online by individuals and institutions who post, share, remix, reframe and comment on such content in ways embedded in the anti-Black market logics of digital virality, clickbait culture, and the clout that may be afforded to brands that allude to their interest in Black and racial justice work but without substantially supporting such endeavours.” — Spectacularized and Branded Digital (Re)presentations of Black People and Blackness, 2021

The aftermath of “spectacularized“ Black death, when captured or disseminated on social media, is in tension with the capitalist logic of how platforms attribute value. It is in the transmission of Black death that the value of content to a platform increases, as it is tightly bound to its increased virality.

Platforms need increased engagement to monetise content. When engagement at all costs is the overriding aim in this scenario, then researchers must be cognisant of the racialised harms that could occur. It is also incumbent on researchers to be advocates for all of the interests of those closest to the deceased.

Platforms rarely survive

My introduction to the internet in the late 1990s started on several obscure message boards, then Geocities, before Web 2.0 brought the social internet and I became an avid user of Friends Reunited. Xanga, Bebo and MSN Messenger soon followed. These services have long since closed down and I struggle to remember any of my user names for these sites.

Digital platforms and services are built with the expectation of lasting forever, but the reality is that the code, plugins or storage media eventually succumb to degradation or obsolescence.

Memorialisation is most commonly an afterthought, initiated as a response rather than part of a design process that considers a person’s whole life and social relations.

“After a person's death, transient communications and platform-dependent profiles can become sacred relics. The production and upkeep of digital remains depend on human and nonhuman actors, from commercial platforms' terms of service, operating systems, and servers to social networks of commenters, mutuals, and surviving loved ones.” — Death Glitch, pg. 3

Death Glitch contextualises how the data, infrastructural and technological oversights existing within digital platforms are emblematic of an industry that has a poor understanding of the social and cultural relations that mediate our use of technology and the intertwined network of friends and family who are essential in maintaining our digital selves. Once we notice the existence of these oversights, they become impossible to ignore.

Design for whole lives

While there are legal frameworks for transferring the ownership of physical assets from one person to another, the same approach cannot be easily used for digital assets. Digital platforms operate across borders. Our data is geographically stored and replicated internationally and the jurisdictions under which they are subject is unclear. It is unlikely that the digital platforms and services, in which we spend years cultivating our digital selves, will survive into our old age. The disappearance of a platform could be the result of an acquisition, business failure, unsupported code, bit rot, or the prosaic reality of extinction due to an ageing user population.

Death Glitch shows how socio-technical research is more necessary than ever. Interventions from designers and researchers must go much further than technology, usability and efficiency. We must be sensitive to how memorialisation is socially enacted and varies by culture or geography. These types of enquiry are crucial in identifying where tensions may emerge between online enactments of grief when they encounter the acquisitive logic of transnational entities that serve as platforms for our digital selves.

Death Glitch: How techno-solutionism fails us in this life and beyond by Tamara Kneese. Published in 2023 by Yale University Press, 257 pages, £27.50.

More from Tamara Kneese

Data Infrastructures of the Dead (from Heliotrope Journal, 2022)

The New Death edited with Shanon Lee Dowdy (University of New Mexico Press, 2022, 352 pages)

Using Generative AI to Resurrect the Dead Will Create a Burden for the Living (from WIRED, 2023)

Dead Links (from Public Books, 2023)

Explore further

On Substack

Kameelah Janan Rasheed writes a segment about death and grief tech in the 17 December edition of their newsletter, I Will (?) Figure This All Out Later, which refers to a man who had a QR code put on his tombstone to document his life achievements.

Listen

Podcast episodes are listed by publish date, then alphabetically by episode title

Transcripts are available for The Lost Cities of Geo, Death, and Hot Take: Can you own your own data?

Resources

Cameron’s World by Cameron Askin is a web collage of text and images excavated from archived GeoCities pages ranging from 1994–2009.

Does Not Compute by Suzanne Van Geuns is a toolkit for historical internet-based research, allowing you to rebuild what online social life looked like in the 1980s, 1990s, or 2000s.

Read

Literature is listed by publish date, then alphabetically by title

Life & Death: The materiality of networks and connected devices by Vladen Joler (from Ding, issue 1, 2017)

The Undertakers of Silicon Valley by Adrian Daub (from LOGIC, 2018)

Facebook could have 4.9bn dead users by 2100, study finds by Matthew Cantor (from The Guardian, 2019)

The Lost Cities of Geo (from 99% Invisible, 2020)

Spectacularized and Branded Digital (Re)presentations of Black People and Blackness by Francesca Sobande (from Television & New Media, vol. 22, no. 2, 2021)

When Black Death Goes Viral: How Algorithms of Oppression (Re)Produce Racism and Racial Trauma by Tiera Tanksley (from Sage Perspectives, 2022)

The art that resets and restores us by Enuma Okoro (from FT Weekend, Life & Arts section, 2023)

Resurrecting the Black Body: Race and the Digital Afterlife by Tonia Sutherland (University of California Press, 2023, 214 pages)

Death glitches – such an interesting topic. That tension between the desire to memorialise and erase a person's digital presence. It's got be thinking about the right to be forgotten that was building steam around 2014.

Obviously we have the Data Protection Act in the UK (GDPR in the EU), which covers personal data collected by search engines, websites and companies. But these traces of ourselves extend far beyond (Tamara Kneese's thoughts about "communicative traces" on social media). Some people think of our contributions as connective tissue, which is a good analogy.

Data feels so atomised on the internet, I am wondering how you would be able to fully opt out of the collective online memory. The logistical challenges of dealing provisions in different jurisdictions. In reality, we may just have to wait for the technology to become obsolete, so we fade away like an old photo out in the open. Or we tread more carefully, tidying up as we go ;)

If I was able to assume control of everything I have contributed to the internet, would I ask for it to be deleted in my will? Probably not. Even the smattering of embarrassing early scribbles, dodgy photos, earnest comments or cringe opening Bumble lines. Let's call it my cultural donation to the world. If it leads to posthumous fame/infamy … so be it. Sorry, mum and dad.