A much-needed handbook to help us relearn how to reconnect with our radical imaginations so we can see past prevailing narratives of technological domination

📚 You can buy books mentioned in this newsletter from my page on Bookshop.org

Who gets to imagine our future? As our relationship with digital technologies becomes more immersive, each successive leap of corporate technology innovation is predicated on delving deeper into our interior being: into our eyes and beneath our skin — each device demanding more attention in the quest to generate monetisable data. We are confronted with technology futures that — for all their talk of innovation, experimentation, and exploration — are the products of ideologies tinged with eugenicist beliefs.

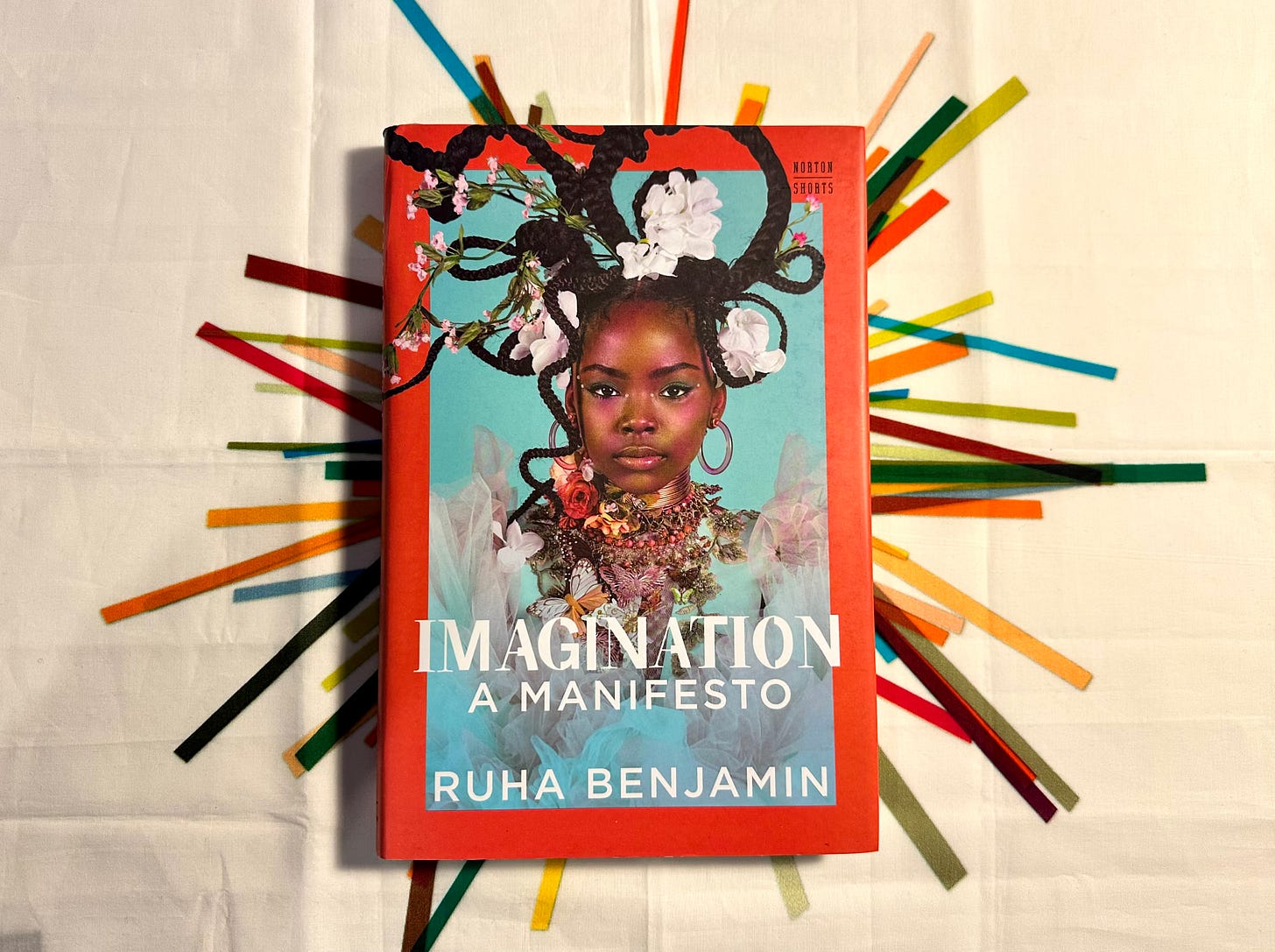

Imagination: A Manifesto, the latest book by Ruha Benjamin is part of Norton Shorts — a series of new titles by leading scholars working across a range of disciplines, presented in books of less than 200 pages.

Benjamin introduces the book by lamenting how imagination — a practice that should be liberatory — has been conscripted by nationalist imaginaries and hobbled by educational orthodoxy.

Anglo-American pedagogy has only incrementally changed since the industrial age. Schools (which should be gymnasiums for awakening and invigorating their students’ imaginations) are predominantly concerned with teaching-to-the-test — a trend that only intensifies as students progress towards university.

The whiteness of our curriculum hurts Black and white children alike — its harm is particularly acute because it lacks safeguards for Black children; while causing those who graduate to have little to no grasp of critical or divergent thinking, and an even looser grip on how the formation of the Western industrialised world was dependent on the exploitation of countries across the Global South.

“If imagination can lead to troublemaking, is it any wonder, then, that those in power work tirelessly to squash us from having radical imaginations that dare to envision a world in which everyone can thrive?” (Introduction, pg. x)

Incremental innovation will only reshuffle the chairs on the deck of an ideological ship that is already listing. By reclaiming radical imagination, we are propelled to think again — not only about how the metaphorical chairs are arranged, but why we are even travelling in this direction in the first place.

Whose imagination?

In 2019, Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello worked with Colectivo Chopeke to install a teeter-totter (a see-saw for my British readers) at the US-Mexico border near Ciudad Juárez and El Paso. The bright pink beams contrast vividly against the dull brown border fence. Each apparatus was used and enjoyed by children and adults alike. Between the vertical metal slats that makeup the fence, we see the outline of what looks like an adult man. Absurd though this juxtaposition appears, the young Mexican boy is sprung high into the air by the weight of an American border force official many times his age and weight. The installation demonstrates in an almost satirical way what each artist terms “the delicate balance between the two nations” — and indeed, the unbreakable interconnection traversing this manufactured boundary.

Discussing this artistic intervention at one of North America’s most tense frontiers, Benjamin writes that “the power of unjust systems lies in their ability to naturalise social hierarchies” (pg. 101). No amount of innovation or adjustment within such unjust systems will result in the realisation of justice. As Benjamin’s thinking develops throughout the chapter — and, indeed, throughout the book — the message resounds. We have an interconnected and interdependent existence. It is useless to erect fences and entrench divisions when an ecological polycrisis and water shortages loom on the horizon — for they respect no boundaries.

Benjamin continues: “We must populate our imaginations with images and stories of our shared humanity, of our interconnectedness, of our solidarity as people — a poetics of welcome, not walls” (pg. 102). Radical imagination asks radical questions. Pursuing answers to radical questions emboldens us to ignore the limitations of creative orthodoxy. Radically departing from creative orthodoxy results in forging a path towards a radical new direction — and it is in the pursuance of these aims that we challenge the mundanity of technological oppression and the prevailing belief that we have no power to arrest its continued expansion.

Interlude: A human decentered future

In my talk “Human Decentered Design” which I delivered at The Conference in 2024, I ask how we can imagine new futures. Today’s technology industry discourse defines the problem and solution as being inseparable from an Anglo-Euro-American perspective — too often eliding the knowledge traditions that have existed alongside and have suffered violence under White supremacy.

Across three parts — Soil, Self, and Sky — I echo many of the themes developed in Imagination: A Manifesto to set out how human domination can and should be decentered while redirecting our attention to the legacies of geological and racial traumas that require healing. I close by setting out a vision for how we can begin to start a dialogue with Black and Indigenous knowledge traditions — each contributing to taking small steps towards our pluralistic futures.

How to future

The final part of Imagination: A Manifesto focuses on how to start making these changes to our thinking a reality. Whether we work alone or in a team; whether we are following each chapter in a formal or informal education, we are taken through scenarios and exercises that show us how to start experimenting with exercising our radical imaginations.

From speculative writing exercises inspired by Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower asking us to imagine the skills we could contribute to a future community; to an appendix filled with suggested starting points for moderating discussions in our own creative projects — Imagination: A Manifesto is a much-needed handbook that equips us with the skills for relearning how to reconnect with our radical imaginations.

We all have imaginations, but too often they employed in the pursuit of oppressive and divisive outcomes. Under pressure to be productive cogs in an extractive machine, we have been trained out of its use. Across these six chapters, Benjamin combines personal recollection and speculative storytelling, backed with empirical evidence and academic rigour, to reassure us that no matter the machinations and technological empire-building looming on the world stage, we have far greater power in our collective imagining, because in her words “… it matters whose imaginations get to materialize as our shared future” (pg. 119).

Imagination: A Manifesto by Ruha Benjamin. Published in 2024 by WW Norton & Co., 192 pages.

More from Ruha Benjamin

Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Polity, 2019, 285 pages)

Captivating Technology: Race, Carceral Technoscience, and Liberatory Imagination in Everyday Life, an edited anthology (Duke University Press, 2019, 397 pages)

Viral Justice: How We Grow the World We Want (Princeton University Press, 2022, 373 pages)

Explore further

Listen

I have been really getting into Radio Web, the podcast series from MACBA. Son[i]a episodes are in-depth interviews with artists, theorists and creative thinkers. Episode #395 from 20 March 2024 is with Imani Mason Jordan. Their responses are stitched together minus the interviewer’s questions resulting in a long-form audio essay that covers a Black feminist perspective on artistic and critical theory, community-building, and world-making. The podcast is not published on Spotify, so you may be able to find it on other podcast platforms, or you can stream directly from MACBA’s website. Published 20 March 2024, lasting 1 hour 13 minutes.

Transcripts are available for Art, Technology and Justice with Yasmine Boudiaf, Alienation from Ourselves, Each Other, and Our Needs, and Imagining 2025 and Beyond with Dr. Ruha Benjamin.

Read

Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds by Arturo Escobar (Duke University Press, 2017, 290 pages)

The Power of Lo-TEK: A Design Movement to Rebuild Understanding of Indigenous Philosophy and Vernacular Architecture by Julia Watson (Common Edge, 2019)

Black Futures edited by Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham (One World, 2020, 542 pages)

Mabel O. Wilson on Radical Optimism (PIN-UP, 2021)

Nick Bostrom, Longtermism, and the Eternal Return of Eugenics by Émile P. Torres (Truthdig, 2023)

An African Feminist Manifesto by Ololade Faniyi (The Republic, 2024)

Mothering Economy by Jenny Grettve (Plastic Letters Press, 2024, 158 pages)

The Alchemy Lecture: Five Manifestos for the Beautiful World by Phoebe Boswell, Saidiya Hartman, Jainína Oliveira, Joseph M. Pierce, and Cristina Rivera Garza, introduction by Christina Sharpe (Alchemy by Knopf Canada, 2024, 168 pages)

The TESCREAL bundle: Eugenics and the promise of utopia through artificial general intelligence by Timnit Gebru and Émile P. Torres (First Monday, vol. 29, no. 4, 2024)

@Afreen look! Tamsin told me about this book. We should read before June!