A journey back to 1977 to witness the turbulent arrangements and joyous staging of the biggest Pan-African cultural festival the world has seen — paying tribute to Marilyn Nance, the young photographer who captured an invaluable visual archive of its proceedings

📚 You can buy books mentioned in this newsletter from my page on Bookshop.org

🔐 No paywall this month — enjoy!

EXT. Street scene, Accra — DAY. Imagine whitewashed two-story buildings lining a busy thoroughfare. Crowds bustling. Hundreds, possibly thousands, of Ghanaians of all ages, rushing to run their errands. Diesel trucks trundle past. Smart two-tone saloons roll by, occasionally tooting. Young boys on bicycles weaving in and out precariously balancing boxes filled with produce for market. Fashionable women in wax print dresses perambulating way along the pavements.

1957. Ghana is on the cusp of regaining independence. The fifties gave way to the sixties. Self-determination, urban development, and cultural expression were pressing concerns as more colonies followed in their journeys towards independence.

Pan-Africanist ideas continued in their growth towards maturity. Africa’s universities were blossoming — students and thinkers collaborated across continents, and ideas flowed between Africa, Europe, and America. Many of Africa’s post-independence presidents studied and exchanged ideas as young students. Ibadan and Dakar to the West; Makerere and Dar es Salaam to the East; Yaounde and Kinshasa in Central Africa; Cape Town and Zimbabwe to the South.

1966. As more African nations gained independence, Senegal’s president, Léopold Senghor, convened the Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres (or, FESMAN) which was also captured in a documentary. Held in Dakar, 30 independent countries took part, and invitations were also extended to diasporic communities in USA, Brazil, UK and beyond. Senghor’s passion for poetry shone through the definition of the festival, which was a demonstration of soft power to articulate the tenets of Négritude. Looking back, Senghor’s definition of who was Black and African feeling essentialist — those from North Africa were excluded. In response, the next festival of Pan Africanism took place in Algiers in 1969, captured by the eponymous documentary Festival Panafricain d'Alger — which had a far more expansive roster that was actively in dialogue with current liberation movements.

1975. Almost a decade passed until a similar exposition of such grand cultural ambition took place in Africa. Nigeria was selected as the host for the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture. These were turbulent times for the young nation. Civil War was a fresh memory, ending only five years prior. Political tensions were high as the balance between military and civil rule teetered leaving successive presidents with shortlived terms.

There is no better way to project the arrival of a young nation than by hosting a global festival. President Mobutu spent millions of his country’s scarce funds to host Zaïre ‘74 culminating with the Rumble in the Jungle.

In a similar vein, President Obasanjo had the luxury of using the newfound riches of Nigeria’s burgeoning oil industry to pledge almost $400 million (over $1.5 billion in today’s money) to ensure the success of this cultural festival. FESTAC was born.

The turbulent road to FESTAC

The Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture was due to take place in 1975. While the first iteration a decade earlier was a more cerebral affair — rooted in literature and poetry — this time around, the new festival was to showcase Pan-African cultural performance. Marcus Garvey’s popularisation of the Back to Africa movement had planted seeds across America and the Caribbean decades earlier. By the time FESTAC was organised, many Black performers in America, the Caribbean and the wider diaspora were keenly aware — or rather, were keenly enthusiastic — of the need to return to Africa to rediscover their spiritual and cultural connections to the Homeland.

Nigerian presidential priorities oscillated as frequently as the men who held office — and the progress of FESTAC’s organisation suffered as a result. 1975 saw a coup and the military president Yakubu Gowon deposed. FESTAC was still due to go ahead, but only just. 1976 and the then president Murtala Muhammed, who was hardly keen on the festival, was assassinated. By the time Olusegun Obasanjo took the reins of power — perhaps as a reflection of his personal vanity or self-interest — FESTAC finally received the government boost it needed to become a reality. Nigeria's oil revenue was multiplying. The naira was strengthening against the dollar, and there was finally political stability in the presidential palace.

As with many modern-era global-scale events, the arrival of FESTAC spurred a flurry of spending for development and construction. A new National Arts Theatre in Lagos was commissioned. Built by Techno Exporstroy — a Bulgarian construction company — it was modelled on the Palace of Culture and Sports many thousands of miles away.

The post-colonial period was a time of construction and urban reshaping, as idealistic architects from Africa and Europe were commissioned to articulate their national ideals in timber, concrete and stone — the resulting buildings combining European architectural forms with local vernacular to showcase innovative approaches to natural ventilation and heat management. What is now termed African Modernism became the architectural language of the cities across the African continent.

The scale of FESTAC would be like nothing seen or hosted in Africa before. Scheduled to last a month with over 17,000 delegates and performers; and more than 100,000 attendees — half a century later, FESTAC still stands as the world’s biggest Black, African and diasporic cultural celebration.

Preparations were turbulent. The early years of Obasanjo witnessed Nigeria experiencing economic turbulence, escalating inflation, and the repression of political activists and critics — most notably Fela Kuti and his mother Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, a renowned women’s rights activist.

Fela and his mother were persistent critics of the military government — Fela famously recorded “Zombie” (1976) to denounce the army. The pair were frequently assaulted and subjected to raids at their home compound — the Kalakuta Republic. The government took note and waited until the eyes and camera lenses of the world had moved on before launching a brutal attack when over 1,000 soldiers raided Fela’s compound on 18 February 1977 (in an ironic twist, the date marked the 80th anniversary of the punitive raid by the British which looted many treasures from Benin). Fela’s mother Funmi, aged 76, was thrown from a second-floor window by soldiers. After a long period in a coma, she died in April 1978 having never recovered from her many injuries.

With violence and the threat of violence looming, it is no wonder that Fela Kuti could not sit idly by to witness Obasanjo manoeuvre to rehabilitate his image on the world stage — and he saw FESTAC as the vehicle the government were using to achieve this aim.

Despite participating in one of the organising committees, Fela was not alone in opposing the motivation behind staging FESTAC and eventually stepped down. Other prominent critics and writers, such as Wole Soyinka, took aim at the government’s profligate spending and corruption. The work of the committees continued without Nigeria’s biggest musical star, and eventually, Fela staged an ongoing counter-festival at The Shrine — his club in Lagos — where he railed against the high and mighty in government on a daily basis. The scale and violence of the subsequent February 1977 raid could hardly be seen as accidental timing. The order to stage this raid must have come from the highest level.

Last Day In Lagos

1977. Marilyn Nance — a young photographer from New York in her early twenties — was studying at the renowned Pratt Institute. She heard about this unlikely festival and was immediately interested in applying to be an exhibiting artist. The vagaries of the application process and initial cuts to the available funding meant she was omitted from the original roster. That didn’t stop her. Through another chance encounter, Nance found out about other opportunities to attend as support staff, and she was eventually accepted to attend as a photo technician.

What an experience! This was Marilyn’s first trip outside of the USA and her first to Africa as part of the official American FESTAC delegation. The practicalities of getting accommodation and settled weren’t entirely smooth, which is forgivable considering that logistics, catering, and medical care were being arranged for tens of thousands of delegates.

2022. During her time in Nigeria, Marilyn took thousands of photos which have now belatedly been collated, arranged and published decades later in Last Day in Lagos (Fourthwall Books/Center for Art, Research and Alliances, 2022), accompanied by her recollections, interviews and essays by other contributors.

“I thought that I would be talking [more] about FESTAC in 1978, not in 2022. I did not know then that it would be disappeared from history. I thought it was something that was so big to me, and to all the other participants, that surely this would be something that would resonate for years and years to come. I think that if something tragic had happened, then everybody would remember, but it was a joyful thing. I guess maybe there was no investment in celebrating Black joy.” — Marilyn Nance interviewed on The New Yorker Radio Hour, 10 January 2023

We have Marilyn Nance to thank for capturing so much of what we visually recall of this remarkable event; what she calls “the paradoxical fugitivity of this tectonic event” (pg. 35) — if you were to describe the turmoil, chaos and unlikely path, by all measures such an event should never have worked.

“Four decades later, if you mention FESTAC to the average Lagos resident, they will point you toward the neighbourhood known as FESTAC Town. If the respondent is in their twenties, they likely could not tell you why that precinct bears its name.” — “Sounds on the Ground” by Uchenna Ikonne, from Marilyn Nance: Last Days in Lagos, pg. 188

I first learned about FESTAC as part of a course on Afrofuturism taught by Dr. Janine Francois in association with Black Blossoms during 2020. Since then I have been avidly seeking out visual artefacts, contemporary accounts and other memorabilia.

It is quite astonishing how an event of such scale, cultural importance and impact can so quietly slip from our collective memory.

Aftermath

“FESTAC was the Olympics, plus a Biennial, plus Woodstock. But Africa style. That was FESTAC. It’s hard to describe, and people have positioned it as science fiction, but it really did happen.” — “A Collector of Selves”, an interview with Marilyn Nance by Oluremi C. Onabanjo, from Marilyn Nance: Last Days in Lagos, pg. 58

After FESTAC was over, Ethiopia was chosen as the next host nation in 1981 but this was derailed by the Eritrean War of Independence, the cost of which weakened Ethiopia’s ability to respond to the famine of the mid-1980s. For many countries across Africa, the spirit of hope and cultural unity was put under immense strain as a result of economic strife, coups and warfare (internally and externally triggered). The optimistic outlook of 1960s African independence, unity, and development morphed into a 1980s that is largely remembered for warfare, coups, and economic turmoil.

Pondering the cultural aftermath of FESTAC 50 years later, it is satisfying to witness how the vehicle of the International Expo was taken back from its colonial origins. Vast shows in Europe and America were put on to demonstrate the colonial spoils of conquest, using the veneer of education to justify display, despite the reality of African artefacts and people being subjected to spectacle and ridicule — a practice that continued in Europe with ”Congo villages” and human zoos remaining as popular attractions as recently as 1958.

There is much to critique in the staging of FESTAC and the enthusiasm of authoritarian regimes — from Mobutu to Obasanjo — in using the veneer of culture, music, and performance to burnish their credentials outside of their countries while domestic critics were imprisoned, tortured or killed. The same tensions persist today as we critically appraise the decisions behind staging the Olympics and World Cup in regimes that have little to no regard for human rights.

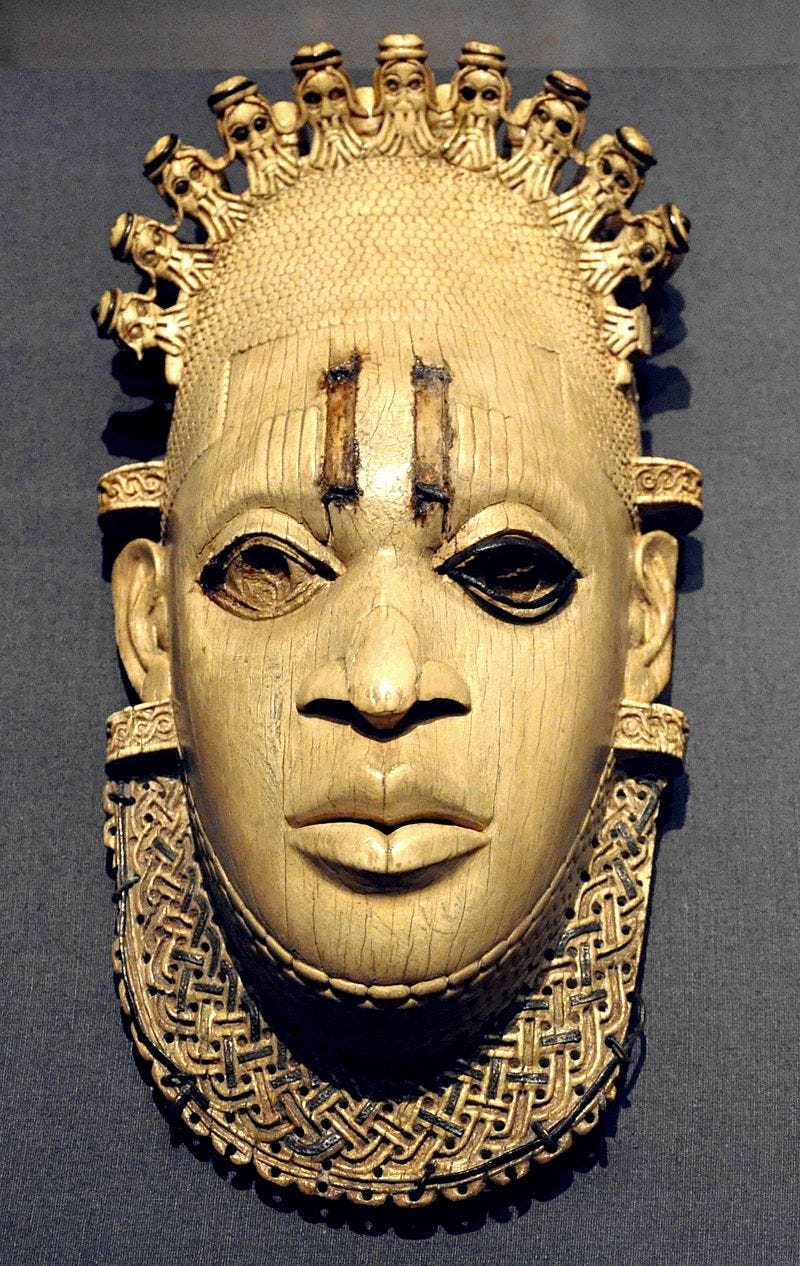

FESTAC never returned after 1977. There is an air of regret that the lasting cultural memory of 1980s Africa is Live Aid. Maybe in this internet-connected age, when we have access to the world’s culture at our fingertips and in our pockets, the prospect of a single exhibition or show might feel outdated. Many of the looted treasures accompanying the Benin mask are being reunited in Digital Benin — with or without European museums’ cooperation. Regardless of our thoughts on how best to project African unity and culture on the world stage, FESTAC should never be forgotten.

Fifteenth #8: On Black creative expression

How the transgressive presence of Black creative expression in music, visual arts and technology expresses Black techno-vernacular creativity and gestures towards new creativity possibilities

Explore further

Listen

The Photographer Who Documented a Long-Forgotten Pan-African Festival (from The New Yorker Radio Hour, 10 January 2023, 17 mins)

Transcripts are available for The Photographer Who Documented a Long-Forgotten Pan-African Festival.

Magazines

Hotshoe #207 (2022, vol. 1): A West African Portrait, £16 (out of print)

Read

Story of cities #5: Benin City, the mighty medieval capital now lost without trace by Mawuna Koutonin (The Guardian, 2018)

Reproducing FESTAC ‘77: A Secret Among a Family of Millions by Ntone Edjabe (The Funambulist, 2020)

The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution by Dan Hicks (Pluto Press, 2021, 376 pages)

African Modernism: The Architecture of Independence. Ghana, Senegal, Cote d'Ivoire, Kenya, Zambia edited by Manuel Herz, Ingrid Schroder, Hans Focketyn, and Julia Jamrozik (Park Books, 2022, 640 pages)

Marilyn Nance: Last Days in Lagos edited by Oluremi C. Onabanjo (Fourthwall Books / Center for Art, Research and Alliances (CARA), 2022, 300 pages)

About the Tropical Modernism exhibition [previously shown at V&A South Kensington, from 2 March 2024 to 22 September 2024]

Heaven on Earth: FESTAC '77 and the Dream of a Pan-African Utopia photographed by Calvin Reid by Miss Rosen (Culture Crush, 2024)

Restitution, wrangling and renewal in Benin by Gisela Williams (FT, 2024)

Revisiting FESTAC ‘77, the largest pan-African festival in World history by Miss Rosen (Huck, 2024)