How a Premier League streaming outage across the East African seaboard reminds us of the fragility of offshore, undersea internet cables; how the architecture of intercontinental internet communications are contemporary desire lines redolent of past colonial extraction

📚 You can buy books mentioned in this newsletter from my page on Bookshop.org

🐳 I will be speaking at Research by the Sea in Brighton on Thursday 27th February 2025. My talk is called “The Spirit of Bartleby: In defence of refusal” — if you want to come, you can use my code JOINMICHAEL at checkout to get a 20% discount!

🗳️ I have submitted my talk “Death, and how tech forgot about mortality” to be considered for the inaugural SXSW London, taking place in June next year. The organisers’ final decisions allow the public vote to be weighted to represent 40% of their final scoring, so every vote counts. You can vote for my talk from the link in my talk title (you need to register for a free account to do this) — thank you! 🙏🏾

Sunday, May 12 2024

Manchester United vs. Arsenal. When two of the Premier League’s biggest teams meet, they are guaranteed to draw a huge crowd. Across the world, millions of viewers stream the match.

Across East Africa — Kenya and Uganda in particular — the Premier League is cult viewing. Downtown bars in Nairobi and Kampala are standing room only whenever Man U or Arsenal play. Even more so when they face each other.

This time, it was not to be. To the frustration of thousands of fans eager to follow every pass, or cheer at every shot, their streaming services let them down. Screens buffered and audio froze. Desperate attempts to find alternative websites were futile.

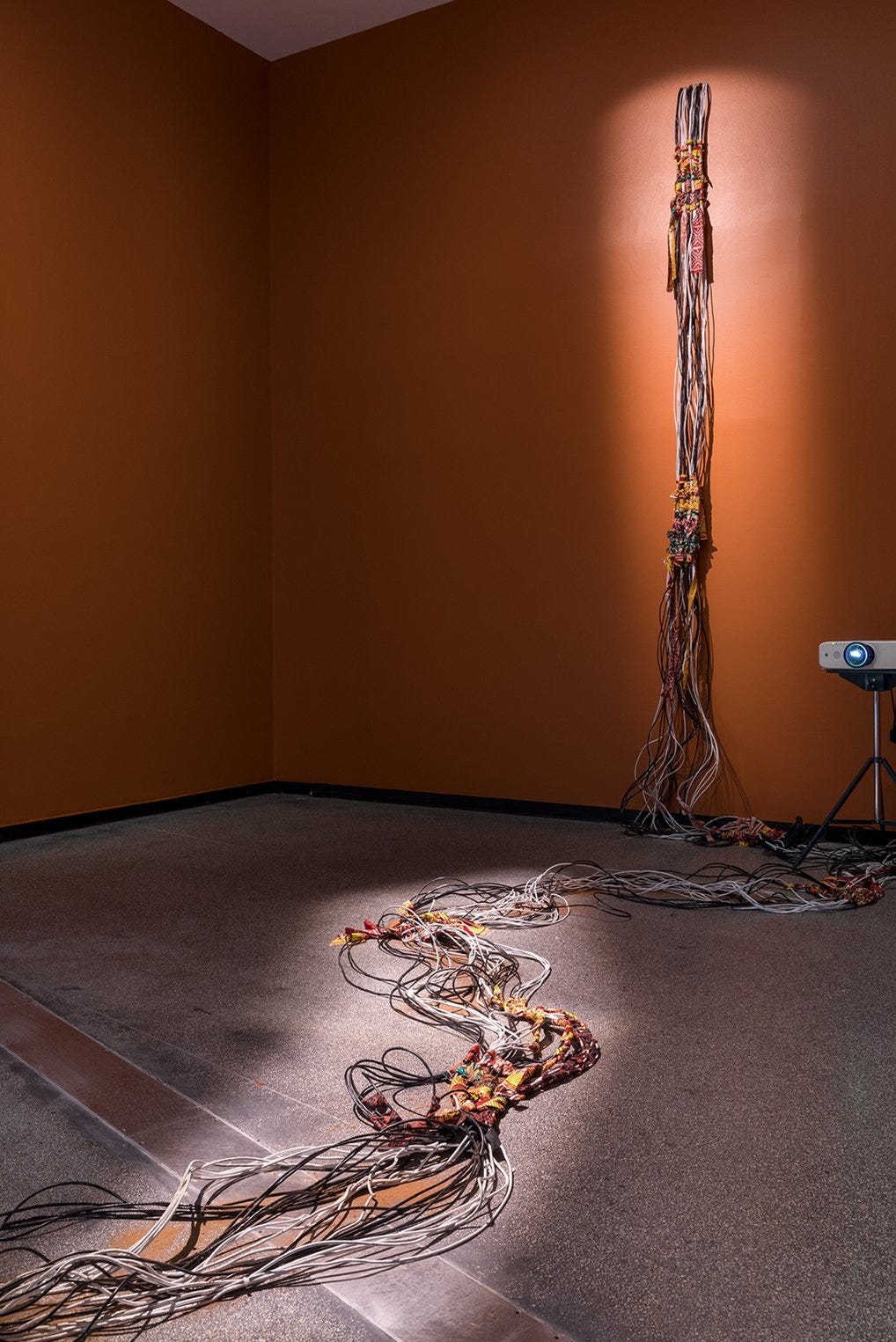

The Eastern Africa Submarine Cable System (EASSy) is a fibre optic cable network laid at the bottom of the ocean. From the south, its connection begins in Mtunzini in South Africa. The cable traces the coastline of Africa, with spurs branching off to provide internet connectivity as it journeys north past Mozambique, Tanzania, and Kenya on the southern and east African coastline before ending in Sudan.

Sometime on Sunday 12 May 2024, part of this cable was cut. The damage was responsible for the loss or serious degradation of internet connectivity affecting approximately 80 million people. It is remarkable to note that internet connectivity to the rest of the world in continental Africa is wholly served by cables that travel around its coast, and as a result, is notoriously susceptible to cascading outages when any part is cut — in March, large swathes of West Africa went offline.

Around the world, damage to undersea internet cables is more commonly accidental — due to errant submarines or a careless dropped anchor from a fishing trawler. On rarer occasions, the damage is deliberate.

We may have never thought about the fragility of internet infrastructures. For a nation to lose its ability to be online, the consequences can be catastrophic — far outweighing the frustration of missing Trossard taking the lead for Arsenal in the twentieth minute.

Outages caused by damaged or cut undersea cables are numerous: banking and trade stalls, emergency services cannot communicate, rural communities are cut off, and governments can no longer cascade messages because communication systems relying on internet connectivity can no longer connect to their data centres.

So, what stories can be told about the topographies of undersea internet cables that — far out of sight — govern so much of how we live and exist online?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to First & Fifteenth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.