Fifteenth #11: On reclaiming futures

Bespeaking our desired futures into existence

An experimental approach where I think out loud and venture into speculative avenues by combining my theoretical influences to articulate what alternative futures mean to me in relation to the land, the past and present

📚 You can buy books mentioned in this newsletter from my page on Bookshop.org

🐚 Early bird announcement! I will be speaking at Research by the Sea in Brighton on Thursday 27th February 2025 where I will be expanding my thinking on digital refusal. Discounted early bird tickets are now available.

💭 This past Wednesday, 13 November, I attended a reading group and screening with Future Inventions Labs on An Introduction to Digital Colonialism. Co-hosted by Yaa Addae and Lex Fefegha in London, with a parallel session in Abuja hosted by Uzoma Urji, we watched Afro-Cyber Resistance by Tabita Rezaire, then read and discussed Amiri Baraka’s Technology & Ethos. So much of Future Inventions’ work aligns with my interests. Next up is an online design workshop on Wednesday 27 November, “Imagining Afro-technological futures”. More reading groups will follow in 2025.

The last three decades of internet culture have seen the privatisation of our internet infrastructure — from the most commonly used technology platforms to internet service providers. Years of corporate acquisitions have reduced administration, access, and control of our digital environment into the hands of fewer and bigger corporations.

The corporate capture of technology’s material and infrastructural realms has operated in tandem with the gutting of news outlets who would have normally had interests in critically reporting on technology corporations. Investigative atrophy has, in turn, diminished journalists’ scope and financial capability for taking the risk to investigate or hold the business of technology to account. As Ruha Benjamin writes in Imagination: A Manifesto, “those who monopolize resources monopolize imagination” (pg. 21).

Possessing and centralising control of internet infrastructures has deleterious effects on our liberatory imagination. Inspired by my reading of Mothering Economy in this month’s review, I want to respond to this sense of helplessness and muse on ways of articulating alternative technological futures.

It is crucial to arrest the drift towards believing the inevitability of privatised futures when the scars inflicted upon Black and Indigenous peoples are barely healed. Prevailing consensus would bid us to move on with no thought of how human-centred economies, accelerated by technological extraction, only thrives in manufactured imbalance — of racialised socioeconomic power, of demand, of agency.

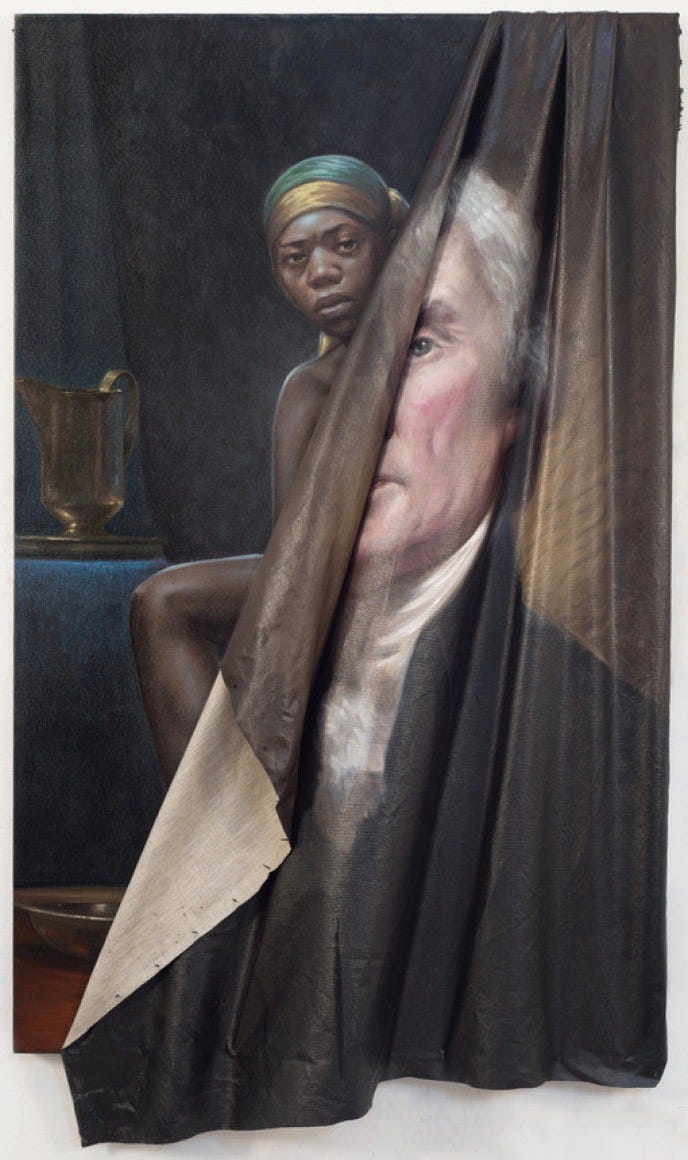

Like a thunderbolt, the message envisioned by Behind the Myth of Benevolence by Titus Kaphar echoes my mood. We understand the metaphor. We cannot avert its gaze. There is a continuity that has marshalled the logics of reduction, centralisation, exploitation, and extraction — bringing each from the plantation and settling them in the modern workplace. As a result, we are experiencing spatial disruption, accelerated by the recent pandemic. We confront these exploitative forces as the shifting demands of the workplace forces a reconfiguration of our living spaces — pushing the negotiation of where and when computer-mediated work is done.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to First & Fifteenth to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.