The story of UK rap and grime which takes us on a journey from London, to the West Midlands, and South Wales

📚 You can buy any book featured in this newsletter from my page on Bookshop.org

🇸🇪 Hej Hej Sverige! The countdown begins properly now… from Tuesday 27th — Thursday 29 August, The Conference gathers in Malmö. I will speak on day 2 as part of the “Rewilding Us” session. I will present my thinking on human decentred design in dialogue with Black Feminist and Indigenous knowledge traditions. Check out the full program and maybe see you there!

🏖️ I am taking a break during August — my next review will be sent on Thursday 1 September. Why not take some time to explore my archive?

UK, not (just) London

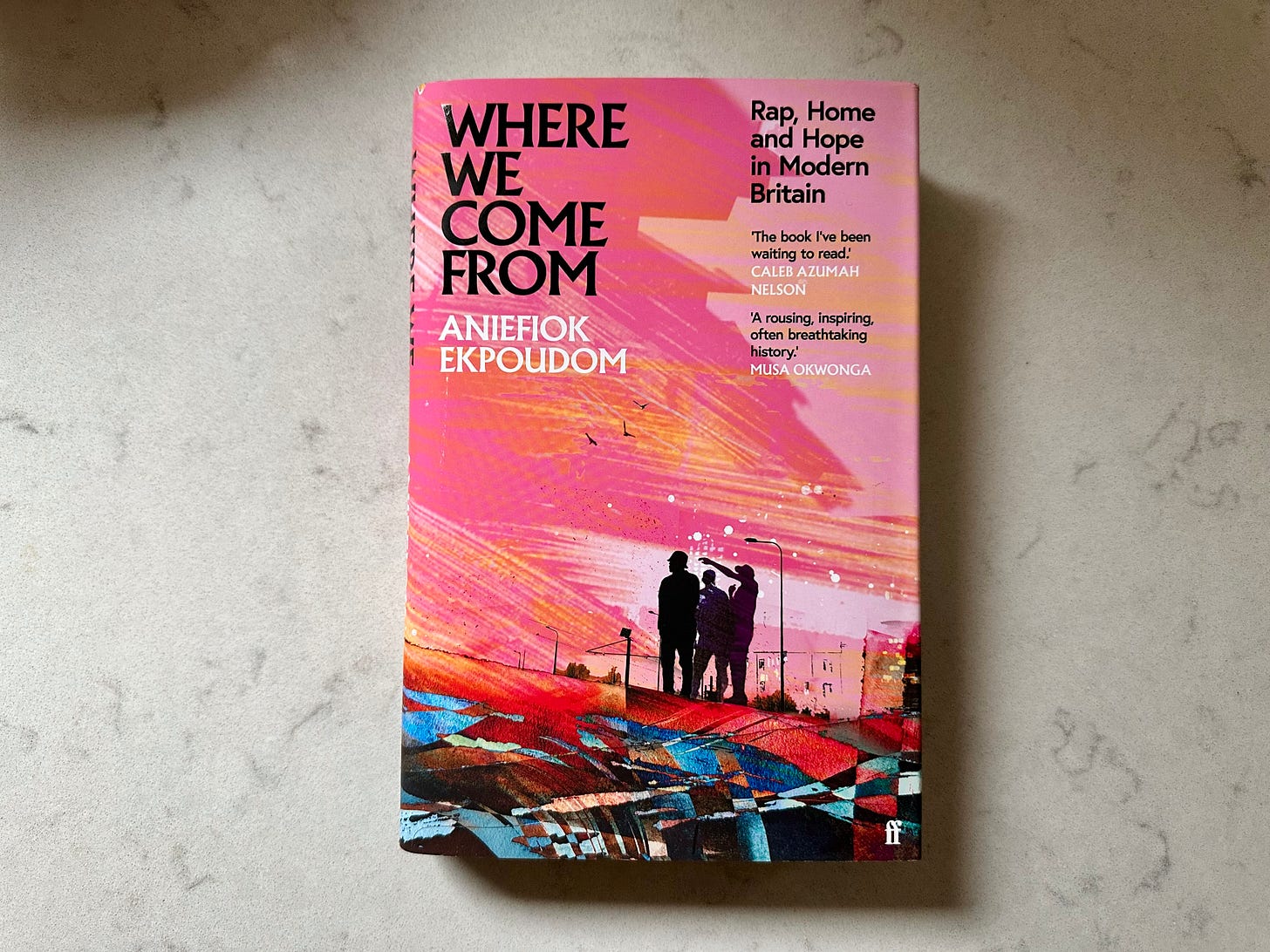

Where We Come From by Aniefiok ‘Neef’ Ekpoudom is an expansive story of UK rap and grime. A product of over 5 years of reporting and research in the Black British music scene, Ekpoudom’s journalistic experience is used to braid a triple narrative that looks past the confines of the M25. We are immersed in the emergence of UK rap and grime, taking in the West Midlands, South Wales, South and East London. Ekpoudom interviews pioneers of Black British music — each conversation surfacing yet another name, yet another place, leading us to another destination to continue the story.

Ekpoudom’s literary inspiration is wide-ranging. He generously shares many of his influences in the Appendix — ranging from James Baldwin, Truman Capote, Joan Didion, to Johny Pitts and more — each informing how he crafts the narrative. Where We Come From is a layered work. From Cardiff to Coventry and Croydon, we are guests beckoned to witness the personal histories of his protagonists, and through their accounts, we get intimately acquainted with the urban environments and social policies that have in equal parts hindered and formed late 20th and early 21st century Black British music.

Music connects communities — traversing distance, language and time — the way we signal connection through rhythm, bass and drum is as old as humanity itself. From the settling of the Windrush generation. From African student populations in universities and polytechnics across the West Midlands, London and beyond. From the growing Afro-Caribbean communities gathering to play soca, reggae, calypso, and High Life. To the post-war British authorities expressing increased disquiet at this visibly different cultural presence. We learn of the earliest attempts to prevent the broadcast of Black music on the national airwaves, giving rise to the first pirate radio stations, such as Radio Starr in early 1980s Handsworth, followed by People’s Community Radio Link (PCRL).

“Rumour is that PCRL became so popular throughout Birmingham that the BBC and BRMB were growing anxious, unnerved at a Pirate Radio station eating into their listenership” — Where We Come From, pg. 21

The story of Black British music in the UK, much like the presence of its African, Caribbean and eventually Black British populations, are testament to competing tensions of cultural alienation, appropriation, and exclusion — both towards and within Black communities.

Grime

Black British music is a by-product of Sound System culture. The interplay between Black British cultures and emerging technologies — of production and distribution — contributed to the music becoming an outlet for successive generations as they grew up within cities that resented their presence.

“Black music genres moving across the strip like high tide, then receding, and dissolving into the ether, leaving room for the next genre to emerge: 2-Tone and Reggae into Pirate Radio and Carnival. Hip Hop into Grime, Grime into Road Rap, and today, in the early stages of a new decade, UK Rap and Drill emerging out of the concrete.” — Where We Come From, pg. 267

There is a cadence to UK rap that sets it apart from its American cousin. Quick-fire lyrical delivery. Syncopated beat — a nod to West London bruk. Again and again, my attention comes back to the technology. Its presence and limited access influencing the produced track.

So much of the Black British music story evades the technological archive. Despite the recency of the featured music, Ekpoudom’s challenge was the inaccessibility and disintegration of the artefacts. The early era of grime and UK rap is preserved on old hard drives, redundant USB sticks, and discarded Nokia phones. Production stories persist in the fading memories of people who just happened to be in a studio.

Aside from being an important work of literature, Where We Come From is a product of archival care work that contributes to the repair of Black British musical memory.

Interlude

Taking up space

The exclusion exhibited towards Black British music, or rather, Black people who make Black British music, operates subtly to a much more devastating effect.

Adèle Oliver, writing in Deeping It, explains how Black British music has been consistently framed as Other, which in turn creates the conditions for its criminalisation; first of the Black performer and then of the spaces we occupy — resulting in rigid controls imposed on venues for hosting Black music for majority Black audiences — justifying surveillance towards artists and those in attendance.

“It almost goes without saying that drill is not the first sound pioneered by Black people to be criminalised by the British government. Jazz, roots reggae and sound system cultures; jungle, acid and garage; as well as pirate radio and grime have all been subject to policing and unfair overcriminalisation on British soil but this is just an iteration of what took place previously in the colonies. Music and dance produced by colonised and/or enslaved Black people across the Black diaspora have historically been perceived as inherently 'pathological or criminogenic' in the eyes (and ears) of the white onlooker. Black music has not been traditionally considered an expressive art form but a dangerous call to arms.” — Deeping It: Colonialism, Culture and Criminalisation of UK Drill, pg. 45

The battle for Black musical expression within our sonic landscape echoes those being fought over our shared urban spaces — a tension that Dr. Joy White explores in Terraformed as she examines the gentrification of Forest Gate, a neighbourhood in East London. Juxtaposed against a constellation of policies and the perceived threats to community cohesion, she defines the intra-municipal bordering of Black presence as “hyper-local demarcation” (pg. 114) — causing young Black people to become aliens in their own neighbourhoods.

Black music is framed as Black noise. The sonic landscape created by Black music is enjoyed while Black producers and Black performers are marked as criminal. Be careful what you say on wax.

“Rap is not normally used by prosecutors as direct evidence of intention or confession (such as a lyric that suggests personal involvement in the specific facts of the crime). Instead, rap tends to be used as indirect or ‘bad character’ evidence to suggest violent mindset, intention to commit serious harm, or gang membership. The evidence is thus typically inferential.” — Compound Injustice: A review of cases involving rap music in England and Wales, pg. 5

Black noise creates the conditions for treating Black music as equal parts wild and hypnotic — a cultural power so alluring, it leads many to believe that by the mere act of hearing it, you too can become deranged and lose control.

“... European hymns were associated with spiritual purity, cultural superiority, musical, tonality, and whiteness; African musical styles were associated with witchcraft, spiritual deviance and cultural backwardness, eternal noise and Blackness… In this way, the colonial technology of racialised Othering is mapped onto soundscapes.” — Deeping It: Colonialism, Culture and Criminalisation of UK Drill, pg. 47

In reaction to Black noise, structural exclusion works to systemically exclude Black performers and the producers instrumental in its creation, so that a more sanitised version can be made safe before its inevitable path to monetisation.

I can count the number of Black-owned clubs in London on one hand. The figure stands in stark contrast to the cultural capital guaranteed by promoting or DJing Black music — occupations that have brought immense profit to the tastemakers who are anointed as the visible face of a sound, who thrive alongside the systemic underrepresentation of their Black counterparts.

In the face of exclusion, innovation flourishes. New promoters continue to look past the confines of our cities. As the appeal of Afrobeats and amapiano continues to grow, events like DLT, Recess and Afro Nation are bringing together younger Black British audiences who are firmly of a social media generation unshackled by the limits of our cities or borders.

Where We Come From goes further than documenting the MCs and producers who have shaped UK rap. The story runs through and beneath the urban landscapes that have both invited and excluded Black British communities who have given so much to shape these sounds. Separating grime from urbanism, licensing policy from door policy — each contributes to determining who has right to take up space in our cities, and in its wake they indirectly gesture to where the next innovations in Black British music will occur.

Where We Come From: an extract

Travelling to South Wales, Aniefiok Ekpoudom writes about his journey to meet Astroid Boys:

“I once took a journey to the old heart of Black Wales. The way to Butetown Community Centre is to head south from the Cardiff Central train station and follow the roads down to the water like a turtle beckoned towards sea. You walk under the railway bridge and across the industrial flats of the A470 roundabout where steel skeletons of new-build apartments and offices staircase the skyline. You walk, as the sun shimmers in a dull sky and the wind wraps around the city like a wet blanket, into an alleyway that leads to a narrow path with a muddy canal running parallel. And as you leave the centre of the city behind, glass-panelled buildings crumble to industrial lots tagged in graffiti, dusty cars are parked, or abandoned, on cracking back roads. Follow the lonely path south, until you see hints of community distilling into view. At the end of the path, you hit a mosque and some low-rise, yellow-brick flats, and then Canal Park where Tiger Bay FC, the local football team erected by first- and second-generation Somali immigrants, play their home games on Saturday afternoons. Their football field marks Butetown pulling in from the near distance. I had reached ground zero, a stronghold, a quiet enclave moored somewhere between the city and the water, historic territory where one of Britain's oldest Black communities claims its home.” — Where We Come From, pg. 149

Where We Come From: Rap, Home & Hope in Modern Britain by Aniefiok Ekpoudom. Published in 2024 by Faber & Faber, 352 pages.

More from Aniefiok Ekpoudom

Skepta, JME, Julie ... are the Adenugas Britain's most creative family? (from The Guardian, 2020)

Four bike rides, four years in the life of Black Britain: ‘On the road, we found ourselves again’ (from The Guardian, 2020)

How south London became a talent factory for Black British footballers (from The Guardian, 2022)

Bait, ting, certi: how UK rap changed the language of the nation by Aniefiok Ekpoudom (The Guardian, 2024)

Explore further

Listen

Watch

Resources

The Black Music Research Unit (BMRU) at the University of Westminster is an interdisciplinary research hub that brings together researchers and academics who are interested in Black British Music, and its lasting influence on culture. If you are in London this summer, you should visit their exhibition, Beyond the Bassline, at the British Library in Euston. It’s on until 26 August. There is also a one-day symposium on Friday 12th July discussing the meaning, histories and legacies of Black British music.

A worrying trend in recent years has been the admission of rap lyrics as evidence in criminal trials. Compound Injustice: A review of cases involving rap music in England and Wales is a report by Eithne Quinn, Erica Kane, and Will Pritchard, published in 2024 by the Centre on The Dynamics of Ethnicity with support from the University of Manchester. This is particularly concerning because of the absence of regulation on how this prosecution tactic is being used in British courts.

Read

Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America by Tricia Rose (Wesleyan University Press, 1994, 257 pages)

Form 696 is gone – so why is clubland still hostile to black Londoners? by Jesse Bernard (from The Guardian, 2018)

Black, Listed: Black British Culture Explored by Jeffrey Boakye (Dialogue, 2019, 416 pages)

The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music by Nina Sun Eidsheim (Duke University Press, 2019, 288 pages)1

Skengdo and AM: the drill rappers sentenced for playing their song by Dan Hancox (The Guardian, 2019)

Terraformed: Young Black Lives in the Inner City by Joy White (Repeater Books, 2020, 164 pages)

Flip the Script: How Women Came to Rule Hip Hop by Arusa Qureshi (404 Ink, 2021, 98 pages)

Ancient Echoes by Zoe Cormier (Zoe Cormier, 2022)

How British Urbanism Shaped Grime by Ric Yeboah (RICHARD YEBOAH, 2022)

Deeping It: Colonialism, Culture & Criminalisation of UK Drill by Adèle Oliver (404 Ink, 2023, 120 pages)

Dizzee Rascal’s Boy In Da Corner turns 20 – here’s how it ushered in the era of grime by Julia Toppin aka “The Junglist Historian” (The Conversation, 2023)

RA.897 IG Culture (Resident Advisor, 2023)

‘They’re doing this by stealth’: how the Met police continues to target Black music by Will Pritchard (from The Guardian, 2023)

Track Record: Me, Music and the War on Blackness by George The Poet (Hodder & Stoughton, 2024, 271 pages)

Why are UK radio stations ignoring Black British music to play recycled American rap? by Elijah (The Guardian, 2024)

Thank you Dr. Eleanor Drage for bringing this book to my attention!