A technocultural examination of the memefication, transmission, and appropriation of Blackness

⛔ Content warning: The second section of this review contains and discusses a redacted image of historical racial violence and lynching.

📚 You can buy books mentioned in this newsletter from my page on Bookshop.org

🎉 On Thursday 10 October, I am teaming up with my friend and fellow design researcher Afreen Saulat of 100Kicks to present “Death and Dating Online: It’s not working, is it?” at SPACE4 in London. Tickets are free, however, they do require advance booking and a refundable £5 deposit.

🎉 Another announcement: On Friday 8 November, I will be presenting “Death, and how tech forgot about mortality” at ffconf in Brighton. I am one of eight speakers at this one day conference. Each talk will be available on their YouTube channel about a month after the event. Until then, go back and read my review of Death Glitch to get a hint of my interest in how digital existence persists after death.

Outro (Adagietto)

Oh Say Can You See

The flag is familiar, but the fabric is tattered. Its dishevelment bears witness to the violence necessitating The Birth of This Nation.

“Oh Say Can You See” (2017) by David Hammons takes the familiar flag and infuses Pan-African colours — red for the blood of the enslaved spilt in pursuit of liberation; black, for a people united; green, in memory of the fertile African lands left behind — each a visual reminder that Black America and her cultures are entwined in the fabric of the nation.

In Black Meme, Liberty Russell draws important historical lessons from the ways that Black culture — and more often than not — Black bodies have become memefied, transmitted, and appropriated. The story of the meme stretches back to the beginning of the last century when communicative technologies became tools for the many. In the American imagination, The Black Body exists as an object of equal parts fascination, exoticisation, and fear.

“Blackness is a deathly myth in the construction of American selfhood... When we engage Blackness as mythology, it becomes open-source material, meaning it can be hacked, circulated, gamified, memed, and reproduced.” — Black Meme: A History of the Images that Make Us, pg. 42

Through Black Meme’s eleven chapters, Russell argues that “Blackness in itself is memetic and, by extension… the technology of memes [is] a core component of a dawning digital culture has been driven by, shaped by, authored by, Blackness” (pg. 12). From Lime Kiln Field Day (1913) — the oldest film featuring Black actors, and a contemporary of Birth of a Nation; to the archival imprisonment of Renty Taylor — a subject examined in the work of artist Sasha Huber (which I wrote about in my essay on archives). We witness the emergence of Thriller as a cultural phenomenon enabled by the availability of home video, to the beating of Rodney King, leading to the dawn of the internet age and the birth of the GIF. In each of these vignettes, we are shown what Russell calls “the copying and transmission of Blackness-as-memetic-material” (pg. 3).

“Blackness-as-memetic material” infuses the cadence, language and rhythm of our most popular social media platforms — past and present. There is a tension that unsettles the operational logic of these platforms which on the one hand, over-polices and disciplines the excess of life expressed by Black creators — as André Brock comments in Distributed Blackness “the devaluation and reduction of the human body to its technical and labor potential are clearest when the body is Black” (pg. 33). Extractive economies that power these platforms have also systemically facilitated the wholesale extraction of Black cultural inventiveness. The violence works both physically and culturally.

In conflict with the culturally extractive demands of Modernity, The Body becomes the site of contestation. As in the past, so it is today — the ways in which we take up space are first a cause of alarm, before becoming a catalyst for suspicion and eventually copied — made safe in a way — so that in the movements of another it can be broadcast.

“… the tradition of Blackness is transmitted somatically—what is embodied, worn and styled, how one moves, speech acts and vernacular utterances, sonic and haptic practices—rather than transferred via the inheritance, or carrying, of valued physical objects as property. Blackness as it intersects with modernity, therefore, has always been the commodity to transmit, and the asset to maximize via viral broadcast.” — Black Meme: A History of the Images that Make Us, pg. 153

Black Meme invites us to critically examine these momentous events in Black culture — each chapter a vignette of how Black American history reverberates into our digital present. Russell’s narrative is a crucial work that interrogates the role of visual communicative technologies, and how they act as catalysts for magnifying violence against The Black Body.

Culture

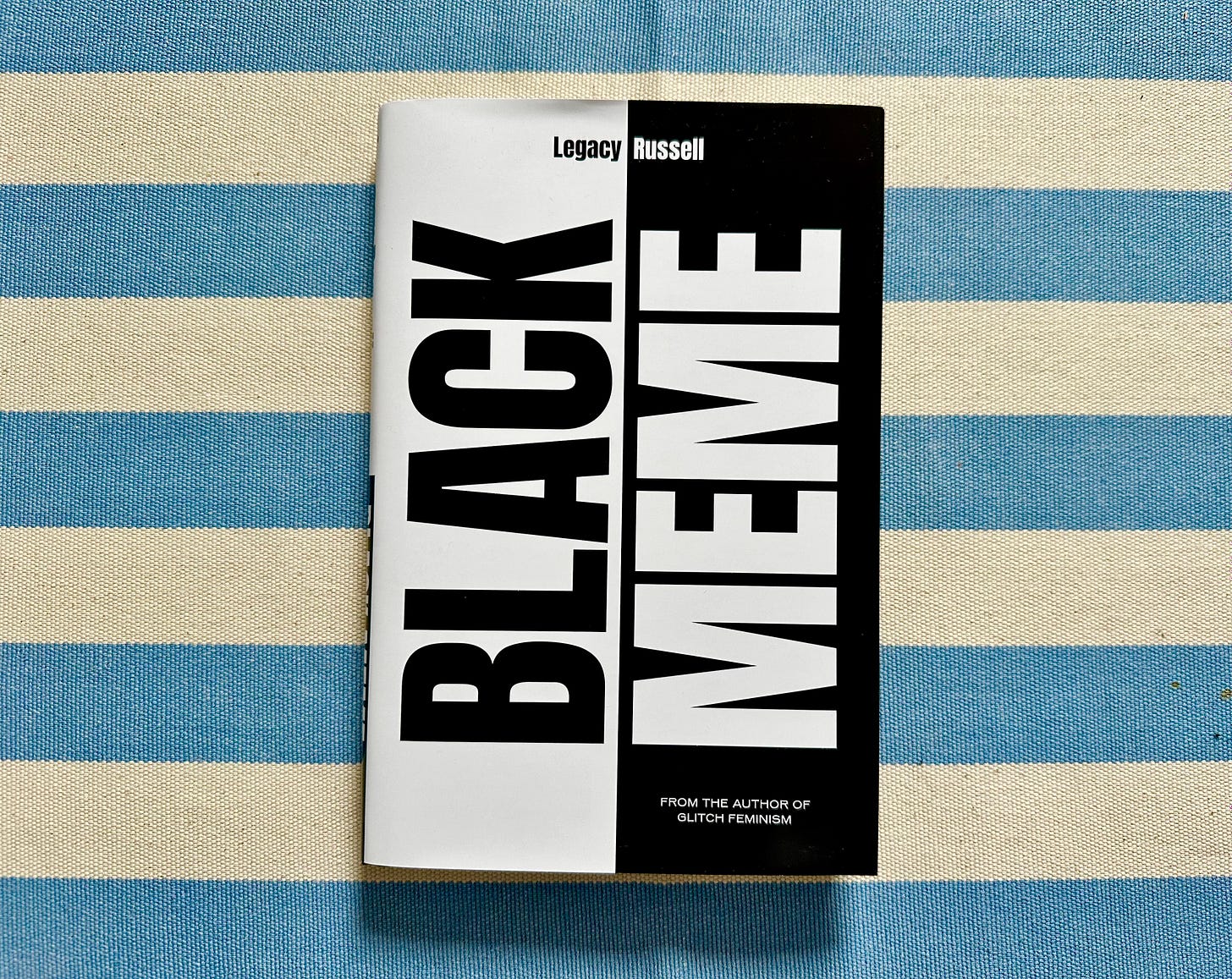

They lynched Allen Brooks.

In the second chapter, we are confronted with a chilling act of racial terrorism. The details are too harrowing to recount. Technology played the role of facilitator to increase the speed of distribution and reach of such acts then, as it does now.

The sequence of events leading to this photo followed a predictable path replayed thousands of times across North America. The rushed court hearing. The verdict reached in less than an hour. Messages relayed to press photographers — some who travelled from far outside of the city — all to ensure they had the best vantage point. Getting the shot would be career-transforming. Printers and distributors on standby, anticipating the imminent surge in demand. Possession of a lynching photo postcard — for those unable to possess shreds of Brooks’ clothes or body parts — became currency. The artefact becomes as social proof of participation representing a token to signal “I was there”.

Black Meme shows us that these acts were not merely hideous acts of violence at the margins.

This was the culture — the spectacle of violence inflicted upon The Black Body and the currency of possessing the moment of ultimate humiliation.

This is the culture because such acts persist in our digital age — except the static image has been animated; doomed to forever play on loop, organised by hashtag.

“... this type of circulated media—souvenirs of hate crimes—is imprinted on our cultural consciousness and is fundamental to the idea of the Black meme. Indeed these images shaped the notion of memetic or viral imagery” — Black Meme, pg. 19

We saw it in 2020 when we witnessed the murder of George Floyd. We see it in the design of social media platforms — only the language has changed. Attention and engagement are the new currency. Russell’s analysis is incisive, steeped in a fluency of Black cultural history that draws important parallels to the way similar logics of exploitation and spectacle are propelled by a visceral lust to republish public humiliation of The Black Body; each combining to fuel the digital economies of our social internet age — what Russell terms as “the promise of harm gone viral [as] an economic strategy” (pg. 47).

Russell’s view is echoed in the work of other Black cultural researchers such as British scholar Francesca Sobande, who writes:

“... images of Black people being killed by [American] police garner over 2.4 million clicks in 24 hours, and the average “cost per click” for related content reaches $6 per click, the virality of Black death is not only incentivized, but nearly guaranteed” — Spectacularized and Branded Digital (Re)presentations of Black People and Blackness

Tonia Sutherland writing in Resurrecting the Black Body: Race and the Digital Afterlife, is more forceful, asserting “the social apparatus of visual media that documents anti-Black violence in the United States [and beyond] is — and has always been — impelled by racism, enabled by technology, and motivated by profit” (pg. 10). Time and again, Black death becomes monetisable content, in the wake of the murders of Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd — each becoming a hashtag and magnet for attention. Each additional comment, a lure for further engagement. The new currency for our social internet age.

In context

From the lynching postcards printed at the dawn of the twentieth century to the viral video in the aftermath of yet another Black life prematurely cut down by law enforcement or vigilante shows how our communicative technologies facilitate the transmission of these images of death, ensuring the currency of their possession and violence of their retransmission remain and reverberate in perpetuity:

“the staging (and restaging) of pain, and its application within digital culture as a garnish to Blackness, has prompted a rise and acceleration of the Black meme” — Black Meme, pg. 150

Black Meme unfolds the narrative of technology as culture — a culture that has been anti-Black for far too long. Perhaps this is what is most searching. For those of us who work in technology and digital design, the dispassionate focus on metrics to improve engagement divorced from their cultural or social context is enough of a salve to excuse our contemplation of the role such platforms play — that we play — in upholding the monetisation and distribution of violence towards The Black Body. We must confront our wilful avoidance of contemplating the design of these economies because we can no longer feign ignorance at the effects these extractive economies produce.

Black Meme: The History of the Images that Make Us by Legacy Russell. Published in 2024 by Verso, 192 pages.

More from Legacy Russell

I first wrote about the Gee’s Bend community in Alabama as part of my previous essay on Black creative expression. The story of Black cultural survival which has endured to the present is remarkable. In The New Bend, Legacy Russell curated an exhibition shown last year at Hauser & Wirth, showing contemporary interpretations of quilt making, in homage to the original quilt makers, described by the gallery as “Black American women in collective cooperation and creative economic production”. Where digital economies have stolen and appropriated so much from Black creative labour, it is reassuring to see how traditional craft has become an accidental site of cultural resistance. It’s a shame I have only found out about this exhibition months after it’s finished!

For anyone in New York, you are in luck! Legacy Russell has been involved with the organisation of this fantastic sounding exhibition: “Distributing Blackness: Reprogramming Internet Art”. Presented by The Kitchen, it is on show at The Schomburg Center until 19 December 2024. I’m an avid reader of André Brock’s work, so the title caught my eye immediately.

Legacy Russell took time earlier this year to discuss the publication of Black Meme with Lou Mensah, the producer and writer behind Shade podcast. Lou’s work has done so much to platform and critically examine Black British art, Black art, and inclusion within the art profession more widely, so it was pleasing to hear them both in conversation. Lou writes at Shade Art Review. I encourage you all to follow, engage with, and support her work.

You may also be familiar with Legacy Russell’s previous bestseller, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, which was published by Verso in 2020 (192 pages).

Explore further

Listen

Catherine Knight Steele, academic and writer of Digital Black Feminism (New York University Press, 2021) outlines some of her insights on the often overlooked influence and agency Black women have played in contributing to the development of what we perceive as digital culture today.

August 2023. You either know it as The Alabama Sweet Tea Party or Fade In The Water. It goes by many names (as viral memes often do). Why do some events become memes and others containing the same elements disappear into the ether? Maybe this is a subject I will return to at a later date. For now, relive one hot Alabama afternoon by the docks.

If you were expecting today’s review to be about Black Twitter, I apologise. 🙏🏾 If you want to engage with research on Black Twitter, follow the work of Dr. André Brock who wrote Distributed Blackness in 2020. I cite it every few months and constantly return to his work to understand what he calls “informational Blackness” and the way that Black culture is expressed in digital environments.

Read

Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity by E. Patrick Johnson (Duke University Press, 2003, 384 pages)

Listening to Images by Tina M. Campt (Duke University Press, 2017, 152 pages)

We Need to Talk About Digital Blackface in Reaction GIFs by Lauren Michele Jackson (Teen Vogue, 2017)

The Undeniable Blackness of Vine (RIP) by Lauren Michele Jackson (WIRED, 2019)

Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures by André Brock (New York University Press, 2020, 271 pages; also available as a free eBook under Open Access)

Paris Doesn’t Always Have to be Burning by Marcos Gonsalez (Public Books, 2020)

A People’s History of Black Twitter: part 1, part 2, part 3 by Jason Parham (WIRED, 2021)

Digital Black Feminism by Catherine Knight Steele (New York University Press, 2021, 208 pages)

(dis)Info Studies: André Brock, Jr. on Why People Do What They Do on the Internet by J. Khadijah Abdurahman (LOGIC(S), 2021)

Spectacularized and Branded Digital (Re)presentations of Black People and Blackness by Francesca Sobande (from Television & New Media, vol. 22, no. 2, 2021)

For Black Folks, Digital Migration Is Nothing New by Chris Gilliard and Kishonna Grey (WIRED, 2022)

Resurrecting the Black Body: Race and the Digital Afterlife by Tonia Sutherland (University of California Press, 2023, 232 pages)

Mortevivum: Photography and the Politics of the Visual by Kimberly Juanita Brown (MIT Press, 2024, 143 pages)